|

|

We were about 200 nautical miles offshore when the voice of U.S. Coast Guard Group San Diego came back over VHF channel 22A. "We've had a meeting and it's been decided to send a helicopter to your position." "Why?" I responded. "What is the reason for doing that?" "You can discuss that with the helicopter pilot when he arrives at your location," was their cryptic reply.

We were about 200 nautical miles offshore when the voice of U.S. Coast Guard Group San Diego came back over VHF channel 22A. "We've had a meeting and it's been decided to send a helicopter to your position." "Why?" I responded. "What is the reason for doing that?" "You can discuss that with the helicopter pilot when he arrives at your location," was their cryptic reply.

The voyage of PANDA to Hawaii had been in the planning and preparation stages for over three years. PANDA is a 1984 Catalina 36, hull #222. The crew consisted of myself (age 56), long time sailing buddy Jack Thomson (age 45), and our teenagers, daughter Aimee (age 18) and Jack's son Jeff (age 19). Aimee had just graduated from high school with high honors. Jack and Jeff are Eagle Scouts. Both Jack and I have 20 plus years of sailing experience and all four of us had attended numerous sailing courses offered by Orange Coast College Sailing Center (Newport Beach, California). I had made a previous crossing to Hawaii on the college's flagship vessel, ALASKA EAGLE, eight years earlier.

PANDA has a manufacturer's published displacement of 15,000 pounds and stated house capacities of 33 gallons of diesel fuel and 48 gallons of fresh water. We added to these, bringing the total capacities to 63 gallons of diesel and 108 gallons of water by using six gallon plastic jerry cans. We carried enough food for more than 21 days. My wife, Phyllis, had packed the meals so that all we needed to do was grab a zip-lock bag containing all the necessary ingredients. She also organized our extensive cruising medical kit that we had purchased from Seaside Marine in San Pedro. Seaside is a well-known purveyor of offshore medical kits. As one of the many preparations prior to departure, our sailmaker installed two additional reefing points as well as reinforcement at critical points of the standard Catalina mainsail.

PANDA has a manufacturer's published displacement of 15,000 pounds and stated house capacities of 33 gallons of diesel fuel and 48 gallons of fresh water. We added to these, bringing the total capacities to 63 gallons of diesel and 108 gallons of water by using six gallon plastic jerry cans. We carried enough food for more than 21 days. My wife, Phyllis, had packed the meals so that all we needed to do was grab a zip-lock bag containing all the necessary ingredients. She also organized our extensive cruising medical kit that we had purchased from Seaside Marine in San Pedro. Seaside is a well-known purveyor of offshore medical kits. As one of the many preparations prior to departure, our sailmaker installed two additional reefing points as well as reinforcement at critical points of the standard Catalina mainsail.

A Bon Voyage dock party, attended by many kind friends and relatives, was held at our home port of Yacht Haven Marina in Wilmington, California, on Saturday, June 27, 1998. We departed on the following day for Kaneohe Bay on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, where a previously leased slip awaited us. With jacklines installed, we left slip #158, which had been PANDA'S home for the past five years, at 11:55 AM on Sunday, June 28. I should make note of the fact that Jack had been wearing a scopolamine (anti-seasickness medication - Ed.) patch for at least 12 hours prior to departure. The rhumb line distance from Los Angeles Light to Kaneohe Bay is 2,221 nautical miles with a compass course of 237 degrees magnetic

Wearing harnesses tethered to jacklines, we headed toward Angle's Gate. It was at this point our first equipment failure occurred. The Genoa fairlead block parted, with the sheave remaining attached to the jib sheet and separating from the portion still attached to the aluminum T-track. With the battery powered drill we had aboard, Jack was able to drill out the defective part and install a fastener to make the fairlead functional again. Less than an hour later we passed by Angle's Gate and began heading for the west end of Catalina Island. Harness's were always worn while in the cockpit and no one was allowed to go forward on deck unless someone was observing from the cockpit. Winds were about 15 knots and the Monitor wind vane (mechanical autopilot - Ed.)was doing a fine job of steering.

Wearing harnesses tethered to jacklines, we headed toward Angle's Gate. It was at this point our first equipment failure occurred. The Genoa fairlead block parted, with the sheave remaining attached to the jib sheet and separating from the portion still attached to the aluminum T-track. With the battery powered drill we had aboard, Jack was able to drill out the defective part and install a fastener to make the fairlead functional again. Less than an hour later we passed by Angle's Gate and began heading for the west end of Catalina Island. Harness's were always worn while in the cockpit and no one was allowed to go forward on deck unless someone was observing from the cockpit. Winds were about 15 knots and the Monitor wind vane (mechanical autopilot - Ed.)was doing a fine job of steering.

For dinner I heated up some previously frozen minestrone soup made especially for us by Jack's wife, Cheryl. What a great treat! Seas were very brisk. Once well clear of Catalina Island's west end, we headed south on a starboard tack, passing San Clemente Island to our port during early Monday morning hours. Sailing was under working jib and with the number 2 reef point installed on the main. It was totally dark that evening and being without radar, hourly GPS positions were plotted to be certain we stayed well off San Clemente. Our closest point to the island was 7.5 nautical miles, although we never saw it in the darkness. From 2:00 AM to 6:30 AM we were heading 201 degrees magnetic and covered 26.7 nautical miles. This works out to an average speed of about 6 knots.

Seas were becoming much lumpier now and the going was not as smooth as we would have liked, but the sailing was good and the boat seemed correctly balanced and was moving well. Late Sunday evening Jack experienced an initial explosive vomiting incident while resting below.

I was in the cockpit when I heard Jack vomiting. Upon entering the cabin, I found Jack sitting up in his berth with a somewhat mystified and surprised look on his face. What greeted me was not a pretty site. Jack very carefully and slowly remove his soaked T-shirt, said good by to it and handed it to me. I told the folks in the cockpit to stand back and over it went! I knew this was not a positive event, but I had no clue as to how serious it would become. The powerful and strenuous vomiting continued and Jack was unable to hold down any solids or liquids.

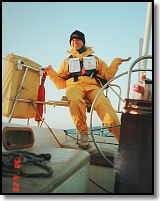

On Monday, June 29, the Monitor windvane failured. One of the guiding sheaves mysteriously disappeared, eventually severing the control lines. We successfully jury rigged a repair and kept on going. Jeff and Aimee had a freeze-dried entree for dinner, a simple faire to which one adds hot water, waits for about 15 minutes, and then eats. Sea conditions were far too vigorous for any type of standard meal preparation. Simple acts such as drinking liquids from a cup were difficult, if not impossible. While trying to drink from a cup it was as though someone had come behind you and slammed a hand directly into your back, spilling the liquid out of the cup over your face, neck and chest. Of tremendous benefit were the pre-packaged drinks in cardboard boxes with a small straw included. Water in plastic bottles with the snap locking tops, along with high-energy food/protein/breakfast/ bars, were also invaluable. A description of going to the bathroom while living in long underwear plus the usual shirts, sweatshirts, pants, and bright yellow foul weather gear would constitute a separate entertaining essay! Log notes say "rough and lumpy, everything wet."

Everything means just that, everything. Cushions, sleeping bags, navigation station, radios, GPS, log notes. Except for the aft cabin, there was not a dry spot in the house. Surprisingly, zip-lock bags, even when securely sealed, can accumulate copious amounts of water. Cans rust rapidly and all our clothing was soaked. What works great is the vacuum bagging machine you see at boat shows. Articles vacuum packed in these bags were not even damp!

At noon Monday, PANDA was about 106 nautical miles from Los AngelesLight on an average bearing of 198 degrees magnetic. Jack continued vigorous vomiting, still unable to take in any food. At 5:00 PM we were 135 nautical miles from Los Angeles Light on an average bearing of 202 degrees magnetic giving us an average speed of 5.8 knots over the past five hours. That evening Jack asked to be excused from his assigned watches with his thought being that a good solid and long rest would help him recover from vomiting. I agreed to this and the three remaining crew split Jack's watch duty.

At noon Monday, PANDA was about 106 nautical miles from Los AngelesLight on an average bearing of 198 degrees magnetic. Jack continued vigorous vomiting, still unable to take in any food. At 5:00 PM we were 135 nautical miles from Los Angeles Light on an average bearing of 202 degrees magnetic giving us an average speed of 5.8 knots over the past five hours. That evening Jack asked to be excused from his assigned watches with his thought being that a good solid and long rest would help him recover from vomiting. I agreed to this and the three remaining crew split Jack's watch duty.

On Tuesday, June 30, we were sailing close to a rhumb line toward Oahu. My log notes once again that the conditions were "rough and lumpy" and that "everything is wet." We were experiencing water over the deck which was finding it's way inside through hatches, dorades, windows, mast member and deck fittings. In sailing the waters of Catalina and environs, we seldom took water on the deck and hence never experienced any seepage that was of any consequence. At 6:45 AM I called home using the ICOM M-710 SSB via KMI on station 809. PANDA was then 205 nautical miles from L.A. Light on an average compass bearing of 2150M. A comparison with our position of the previous day at this time showed we had covered a distance of 143 nautical miles in the past 24 hours with an average speed of 6 knots. The connection was excellent and I reported all was well. In reality all was not well. In addition to our soaked interior, the seas were remaining exceptionally lumpy with numerous large "graybeards" frequently giving us great broadside "wacks" and 25 knot winds. Jack's long rest had not helped and he continued strenuous vomiting. Whenever he was able sit upright, Jack was constantly trying to get into a position so that the pain in his chest was not so severe. The significance of this was unclear at this point, but it did concern me.

I attempted to get weather faxes using the SSB connected to a laptop computer using PC HF Facsimile Ver 8.0 This combination had always worked fine in the past, however this time the computer refused to recognize the program, instead displaying curt and meaningless messages. Consequently, we were never able to get weather fax information.

A comparison of noon fixes at this time showed that PANDA had just completed a noon to noon run of 144 nautical miles. Of particular interest was the location and movement of tropical storm Blas which was coming up from the tip of Baja. We were able to contact a passing U.S. warship on VHF Channel 16 at 1:26 PM and they kindly gave us the latest scoop on Blas. We were informed that Blas was at 18.00N and 122.00W and was moving in a direction of 250 degrees at 12 knots and was packing winds speeds of 100 knots. Although this reported position puts Blas approximately 800 nautical miles directly due south of our position, we speculated that the rough, sloppy and confusing seas we were experiencing were in part due to the effect of Blas.

A comparison of noon fixes at this time showed that PANDA had just completed a noon to noon run of 144 nautical miles. Of particular interest was the location and movement of tropical storm Blas which was coming up from the tip of Baja. We were able to contact a passing U.S. warship on VHF Channel 16 at 1:26 PM and they kindly gave us the latest scoop on Blas. We were informed that Blas was at 18.00N and 122.00W and was moving in a direction of 250 degrees at 12 knots and was packing winds speeds of 100 knots. Although this reported position puts Blas approximately 800 nautical miles directly due south of our position, we speculated that the rough, sloppy and confusing seas we were experiencing were in part due to the effect of Blas.

Late Tuesday afternoon Jack informed me that he had vomited up blood. I asked how much and he replied "about a tablespoon." It was about this time that he removed the scopolamine patch, figuring that it was pretty useless. We talked for a few minutes more and then he began coughing and vomited/spit up more material into the galley sink. I had never seen expectorant of this nature. It was black and looked like a mucous cobweb covering the entire bottom of the sink and looked like something out of a scary Halloween movie. I guessed it was dried blood in mucous. This worried me greatly. I did not know what was specifically wrong, but I felt the situation was serious.

Miraculously, I was able to contact USCG San Diego (CGSD) via VHF radio on Channel 22A and request medical advice. Fortunately, VHF is not always strictly line of sight. This communication covered a distance of almost 300 nautical miles and comms were excellent. CGSD contacted a medical resource and informed us that Jack could begin to take Meclizine, 25mg tablets (which was the only seasickness medication in our first aid kit). They also advised that we should at once abort our trip and return to port and immediately seek medical attention for Jack. No diagnosis was given, but he repeated the medical advice. Jack heard this entire conversation, as he was standing right next to me.

We were also told that there were no contraindications in taking Meclizine even though the Scopolamine patch had recently been removed. Jack was able to swallow, but unable to hold down the Meclizine.

Aimee and Jeff were in the cockpit. Standing by the nav station, Jack and I discussed turning back to port. Jack asked for more time to stabilize, looking sad and upset. He suggested we stay our present course for the night and then see how he was doing in the morning. I countered this by saying that by then we would be another additional 70 nautical miles or so out and that if he was unchanged or worse, we'd then have a further distance to go back. I told him that I didn't know what was going on with his vomiting, but that I did know vomiting up blood was serious and nothing we should be gambling with. At this time I remembered months earlier being in Jack and Cheryl's home. Cheryl and I were standing alone at the kitchen sink talking about the upcoming trip. She turned and looked at me and said "You just make sure they get back home alive." Risking Jack's health simply was not an option in my mind.

As a compromise, I recommended that we begin heading back immediately and if in the morning he was better, we would once again turn around and continue our trip. If he was not improved, then we would have 70 miles or so less to go to get him medical aid. He agreed to this. I was relieved, since I was not going to gamble with his life. I didn't want to bury my best buddy at sea with his son watching.

We were 21 nautical miles closer to Los Angeles than to San Diego. At 6:30 PM we tacked PANDA, changing from starboard tack to port, and began heading back with a compass bearing of 42 degrees magnetic. Our position at this time was 31008.6 N and 122045.3 W, a distance of 275 nautical miles from L.A. Light. At that point we were 1, 968 nautical miles from Kaneohe Bay and that was as close as we were to get.

The return sail toward Los Angeles Tuesday evening and Wednesday morning, July 1, was through rougher and sloppier seas. Winds were at 30 knots frequently gusting to 35 knots. Jeff was clearly worried about his dad, repeatedly expressing his concern about his well-being. Jeff wasn't alone in his feelings; we were all apprehensive about Jack's condition. On port tack PANDA was clearly taking on more water. Being below decks was like being in a tropical rain forest, except for the fact that it was cold. Duffel bags and the once dry clothing in those duffel bags were not merely damp, but soaked. I had spent the last 15 hours in the cockpit, not wanting to leave Jeff or Aimee alone (they were alternating shifts, covering for the ailing Jack).

Upon entering the main cabin at about 9:00 AM Wednesday morning, I discovered several inches of water covering the cabin sole. The water was sloshing about, staying mainly on the starboard side of the vessel. We estimated the total volume to be about 20 gallons. It was difficult, if not impossible, for the bilge pump centered amidships to grab any of this water and pump it out as most of it tended to stay on the starboard side. In a vessel of this design and under these conditions what is really needed is separate port and starboard bilge pumps as there is no deep centered bilge directly above the keel area that would enable the centrally located bilge pump to remove the water. We began working with manual pumps. After a little more than an hour, most of the water was removed, but we could tell more was continuing to come in.

All the seacocks and through hulls were examined, but no leaks were observed. I then noticed that the bathroom shower sump was overflowing with water. Looking up, I quickly discovered the reason why. Unbelievably, the port jib sheet had become caught under the external lip of the bathroom deck hatch and had actually lifted it up, even though the hatch latch or "dog" was still firmly in place. Unable to loosen the latch "dog" with bare hands, a pair of channel locks wasnecessary to do break loose the latch. The hatch was opened and the jib sheet was freed. I then securely closed the hatch, thinking this freaky problem would not likely occur again. What wishful thinking! About two hours later the hatch was completely opened by the same jib sheet, only this time the latch assembly was broken, lying in pieces on the floor.

At about 1:00 PM, concerned, I once again called CGSD simply to alert them to our situation. I stated that we were in no immediate danger, but did want to establish communication with them as a safety measure. CGSD, remembering who we were from our previous call the day before, took down all our pertinent information and our location. We agreed to maintain 30-minute check-in periods.

We continued our 30-minute check-ins with CGSD, relating that water was coming in, but that we were able to keep up with it. About once an hour we needed to man the pump to remove the accumulated water. At about 2:30 PM, with our jury-rigged Monitor windvane steering, a large wave hit PANDA and threw her off course, accompanied by a loud "whoomp." She did not, as usual, return to course. Jeff released control of the Monitor from the steering wheel and attempted to manually steer the boat. It was immediately apparent that he had no control of the vessel. Upon opening the lazarette, it was clear that the steering was broken and not repairable. This was an Edson steering system and the cast aluminum conduit bracket had completely snapped apart in two places, allowing the steering cables to fall off the radial drive wheel. This left us without any immediate way to control steering via the wheel. I handed Jeff the emergency tiller and, sitting down on the floor of the cockpit and bracing himself, he was able to continue sailing on course.

We continued our 30-minute check-ins with CGSD, relating that water was coming in, but that we were able to keep up with it. About once an hour we needed to man the pump to remove the accumulated water. At about 2:30 PM, with our jury-rigged Monitor windvane steering, a large wave hit PANDA and threw her off course, accompanied by a loud "whoomp." She did not, as usual, return to course. Jeff released control of the Monitor from the steering wheel and attempted to manually steer the boat. It was immediately apparent that he had no control of the vessel. Upon opening the lazarette, it was clear that the steering was broken and not repairable. This was an Edson steering system and the cast aluminum conduit bracket had completely snapped apart in two places, allowing the steering cables to fall off the radial drive wheel. This left us without any immediate way to control steering via the wheel. I handed Jeff the emergency tiller and, sitting down on the floor of the cockpit and bracing himself, he was able to continue sailing on course.

At this point I informed CGSD that we had the flooding situation under control, but had lost our steering and were now using emergency tiller. CGSD responded, apparently after some thought, that they were sending a rescue helicopter to our location. I asked what the purpose was and was told that the pilot and I would discuss that when they arrived on scene. CGSD asked if there was high frequency (HF) radio capability on board. I replied in the affirmative and was asked to turn on the SSB and switch to 2182 kHz. I turned on the SSB , however once on the requested frequency I noticed that the point of attachment where the microphone joins into the body of the radio was snapped off. No HF today, folks! Returning to VHF, I informed CGSD that we would have to continue along on channel 22A. Lucky for us, VHF communications continued to work fine.

At approximately 3:50 PM a Coast Guard HH-60 Jayhawk helicopter, number 6008, arrived on site. Our location was 32017.9N, 120033.0W, approximately 143 nautical miles from L.A. Light. We were instructed to drop all sails and maintain our vessel's speed and direction under diesel power. The Harken roller furling refused to work and we were unable to roll in the jib. Unknown to us at the time, the three torque tube screws had managed to work themselves free and were long gone. This rendered the roller furling useless. We manually took down the jib sail and stored it below.

At this point the pilot gave us two options. Option 1 was to abandon ship. This option was strongly encouraged as 35-knot winds and 20 foot seas were predicted for that evening. We were told that it would be much easier to rescue us at this moment than it would be to do so at 2:00 AM that night in darkness and high seas. Option 2 was that they would drop us two gasoline driven pumps and a rescue swimmer. The rescue swimmer would come aboard and instruct us on how to operate the pumps. After giving us operation instructions, he would return to the helicopter, which would then return to its base.

At this point the pilot gave us two options. Option 1 was to abandon ship. This option was strongly encouraged as 35-knot winds and 20 foot seas were predicted for that evening. We were told that it would be much easier to rescue us at this moment than it would be to do so at 2:00 AM that night in darkness and high seas. Option 2 was that they would drop us two gasoline driven pumps and a rescue swimmer. The rescue swimmer would come aboard and instruct us on how to operate the pumps. After giving us operation instructions, he would return to the helicopter, which would then return to its base.

In an earlier conversation with CGSD, we were informed that a Coast Guard vessel was on its way to our position in order to accompany us back to L.A. It was scheduled to arrive at our location sometime after midnight. Shortly thereafter CGSD canceled this mission because their vessel was encountering exceptionally rough seas and one member of the crew had fallen and seriously injured himself. They had chosen to anchor off San Clemente Island until things calmed down.

The pilot made it clear that the decision was completely ours, but his strong recommendation was for us to select the first option. I decided to follow the Coast Guard recommendation and after confering with the pilot told everyone we needed to get out of our foul weather gear and put on life jackets as he requested. Once we agreed to go with Option 1, we were told to turn off the engine and deploy our four-person Givens life raft. After deploying the raft and bringing it as close as possible to the boat we then left via the stern rail and swam to and entered the raft.

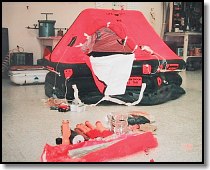

Fortunately, Jeff went first. I say fortunately because Jeff was an outstanding water polo player and swimmer in high school and is in tremendous physical shape. Opening and entering the Givens raft was not easy. The lettering on the entry door instructs you to "push" it open. This will not work at all. The Velcro seal would not give way. Jeff was pushing and shoving at the doorway, all the while in high seas. Jeff realized that a tremendous full body wallop would be required to break the Velcro seal. As a final supreme effort, Jeff soared up into the air and came down with all his might on to the door, plunging his fist directly into its center. Miraculously, the Velcro parted. Once the seal was broken, the door opened readily and Jeff was able to enter the raft. Aimee went next, followed by Jack, and lastly by me.

Fortunately, Jeff went first. I say fortunately because Jeff was an outstanding water polo player and swimmer in high school and is in tremendous physical shape. Opening and entering the Givens raft was not easy. The lettering on the entry door instructs you to "push" it open. This will not work at all. The Velcro seal would not give way. Jeff was pushing and shoving at the doorway, all the while in high seas. Jeff realized that a tremendous full body wallop would be required to break the Velcro seal. As a final supreme effort, Jeff soared up into the air and came down with all his might on to the door, plunging his fist directly into its center. Miraculously, the Velcro parted. Once the seal was broken, the door opened readily and Jeff was able to enter the raft. Aimee went next, followed by Jack, and lastly by me.

It is interesting to note that not one of us was able to see or use the boarding ladder upon attempting to enter the Givens raft, which this unit supposedly had. It probably was there, uselessly dangling. This was unfortunate, as a boarding ladder would have been of great help in this situation. Also, entering the raft while wearing a life preserver is no easy task. The two large packs on your chest make it difficult to slide yourself into the raft.

Prior to leaving PANDA, I activated the ACR Electronics 406 MHz EPIRB as requested by the CGSD. This would make it possible to track the movements of PANDA. Using the knife included with the raft, the line connecting the raft to PANDA was severed and the raft containing all four of us drifted out and away. Moments later we saw a snorkel go by the front of the raft and then a smiling and cheery face popped up. "Hello" he said. "My name is Eric and I'm your rescue swimmer. Are you having a good day?" This immediately broke the tension as we all burst out laughing, with Eric energetically shaking each of our hands.

One by one, Eric swam us to the rescue basket. We got into the basket, momentarily ducked our heads, and went for a quick one or two hundred foot ride into the helicopter. First Jack went, then Aimee, and next Jeff. While drifting about alone in the raft I made two observations. One, I looked at my watch and the time was 4:20 PM. Secondly, I realized I wasn't at all scared. But I do get scared now, when I think about it, talk about it, write about it, or watch the training videos the Coast Guard made during the operation.

One by one, Eric swam us to the rescue basket. We got into the basket, momentarily ducked our heads, and went for a quick one or two hundred foot ride into the helicopter. First Jack went, then Aimee, and next Jeff. While drifting about alone in the raft I made two observations. One, I looked at my watch and the time was 4:20 PM. Secondly, I realized I wasn't at all scared. But I do get scared now, when I think about it, talk about it, write about it, or watch the training videos the Coast Guard made during the operation.

Just prior to my departure from the raft and swim to the rescue basket, Eric said he needed to sink the raft. He pulled out his knife and put large slits in the inflation tubes. The raft continued to float (it doesn't sink very rapidly) and I rolled out into the ocean and went with Eric to the rescue basket. Good-bye PANDA. It would be six anxiety filled days with a telephone stuck in my ear from dawn 'til dusk until I would see her again.

Off in the distance we saw a fixed-wing LC-130 Hercules circling about. It was acting as a backup in case the helicopter experienced difficulties.

Once aboard the helicopter, we were cold as well as wet. We were given blankets, juices, candy and our blood pressure was checked. Helicopters are incredibly noisy and normal conversation was impossible. We communicated by hand signals, written notes, and intercom head sets. We gave our home phone numbers so our spouses might pick us up at the San Diego Coast Guard station later that evening. The flight back to the Coast Guard home base took about 45 minutes.

Once aboard the helicopter, we were cold as well as wet. We were given blankets, juices, candy and our blood pressure was checked. Helicopters are incredibly noisy and normal conversation was impossible. We communicated by hand signals, written notes, and intercom head sets. We gave our home phone numbers so our spouses might pick us up at the San Diego Coast Guard station later that evening. The flight back to the Coast Guard home base took about 45 minutes.

After landing we were requested to remain in the helicopter to allow time to prepare the Coast Guard personnel and officials for our arrival. We were told the press had found out about the rescue and would want interviews. Once all was in place, we we disembarked from the helicopter. We all had our "sea legs" by this time and found walking on land slightly awkward, but we got over that eventually.

We thanked all the Coast Guard people for their help and went on to get warm showers, dry clothes and sandwiches, stopping on the way to be interviewed by reporters with their many microphones and video cameras. Each of us expressed our gratitude to all the personnel of helicopter 6008. Coast Guard personnel very kindly offered to do our laundry. Showers completed and wearing Coast Guard jump suits, we were standing in the aircraft hanger area when we all caught a strong whiff of something reminiscent of brunt toast. The dryer with our clothes in it had just caught on fire! It was a symbolic grand finale to this great adventure.

The following morning Jack was examined by his physician. He was still having serious pain in the center of his chest and experiencing inability to swallow solids. The diagnosis was that Jack had a tear in his esophagus caused by a combination of strenuous vomiting and stomach acid getting into the esophagus. A friend who is a physician and a gastroenterologist, informed me that about 10% of these cases prove fatal. Not good odds at all in my book. A week after leaving PANDA at sea, Jack was still having difficulty in swallowing, but improving daily. A little over a month later Jack was given a clean bill of health by his physician.

The following morning Jack was examined by his physician. He was still having serious pain in the center of his chest and experiencing inability to swallow solids. The diagnosis was that Jack had a tear in his esophagus caused by a combination of strenuous vomiting and stomach acid getting into the esophagus. A friend who is a physician and a gastroenterologist, informed me that about 10% of these cases prove fatal. Not good odds at all in my book. A week after leaving PANDA at sea, Jack was still having difficulty in swallowing, but improving daily. A little over a month later Jack was given a clean bill of health by his physician.

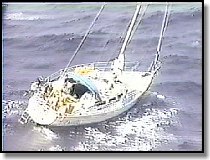

PANDA continued to drift about on her own for days and was observed at various times by military as well as private aircraft. Without going into endless detail, and it is endless, I will simply state two points. Point one is that it is not an easy task to get an insurance claims adjuster, insurance surveyor, United States Coast Guard, and a private tow company to all speak on the same wavelength. Trying to do it on a July 4th weekend makes it all the more challenging.

Point two is that that there were "pirates" out there trying their utmost to find and claim PANDA as their own (for salvage rights). Some reputable and very well know organizations were going out to get her, indeed even after they were told to "lay off" because another commercial towing service had been contracted to retrieve the vessel. To this they responded "may the best man win." Leaving your boat alone and out at sea is a very serious and high-risk business. Even after the Coast Guard specifically states that the vessel is not abandoned and her recovery is in progress, there are those who wish to reap great profits at the misfortunes of others. This is especially incongruous when their ads in sailing publications and brochures in chandlries would have you believe they are your boating friend.

Luckily, the story ends happily. PANDA was finally found by the contracted commercial towing service, using the services of a spotter aircraft, on Sunday, July 5 at 2:30 PM. Her position at that time was 30032.34 N and 119037.64 W, 203 nautical miles from L.A. Light. She had been wandering out in the ocean for 4 days and was 116 nautical miles SSE from where we initially parted. PANDA was back in her original slip at Yacht Haven Marina in Wilmington by noon, Tuesday, July 7, 1998.

Considering what she had been through, PANDA was in amazingly great shape. There was some damage to the dodger, the cellular phone was soaked with salt water and beyond repair, the ICOM M-710 SSB has no sound (an installed and functional microphone is required for operation), and all cushions need professional cleaning. A vertical member of the stern rail on the port side had snapped off at the base. Could the fact that we had an outboard motor and a spare forty-pound propane container hanging there plus using it as an attachment point for the roller furling as well as the Monitor windvane have caused this to occur? Probably!

Two final interesting facts: One, we noticed during our voyage that the water in our house water tanks was tasting particularly salty. Pretty yucky! We all speculated as to how this came to be. Days later, back in port, Jack was doing a wash down and noticed that water flowing over the end of the gunwale on the port side had bubbles in it, right by the fresh water inlet fill cap. When he stopped pouring water down the gunwale he noticed that the water standing over the fresh water inlet rapidly disappeared. Conclusion: a leaky fresh water cap, sans o-ring, allowed the salt water contamination of all 48 gallons of house water. Secondly, in an effort to hold the rudder amidships during the return tow back to Los Angeles, the salvers tied off the tubular aluminum emergency tiller in the amidships position. After a few miles the emergency tiller snapped in half. Just another of the many sailing gotchas.

Ending on a positive note, Jeff summed it up best for all of us when he said "This was the finest sailing I've ever experienced and some of the scenes were just beautiful!" Aimee's comment was "It's too bad the adults were worried. Jeff and I were having a great time!"

So, what did you do that was interesting and different this summer?

NOTE: Further information about the incident and comments about lessons learned below were obtained via a series of email exchanges with the author after receipt of the story above.

All's well that ends well certainly describes this adventure. No lives or even a boat lost and some excellent lessons learned. Said Rowe, "This is an experience that I think about almost on a daily basis. I'm constantly reviewing the entire experience over in my mind, replaying each step, each new development and how I might have handled things in a different manner."

Preparation is always critical. The further offshore you venture, the more critical it becomes. It is clear that Rowe took pains to make sure that they were equipped with better quality safety and survival equipment and that safety overall was a serious consideration. Witness the expense of the Givens life raft, 406 MHz EPIRB, professionally assembled medical kit and the strict PFD/harness rules to name but a few obvious clues about such an attitude for which Rowe is to be commended,

However well prepared they were in other areas, PANDA herself turned out to be not quite up to the challenge of blue water sailing. While every long passage seems to bring its share of failures and annoying inconveniences, in this instance many would appear, with the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, to have been preventable. Pre-departure checklists are available from a variety of sources, but they are just a place to start. Bottom line is that the boat needs to be gone over with a fine tooth comb from bow to stern, leaving not even the smallest piece of equipment uninspected or renewed, as appropriate.

Some of the failures were issues of maintenance, such as the missing o-ring on the fresh water tank filler cap. Had the voyage continued, this would certainly have created a difficult situation. In a few more days their only potable water would have been what was in the plastic jerry cans on deck. Rowe was wise to have provided that additional water in auxiliary containers. It is always a good idea to have multiple separate sources of fresh water (a desalinator is another viable option as a redundant source to stored water) in case one or more becomes contaminated, by whatever means. Note however, that in extreme conditions anything stored on deck may be lost. Something to consider if you know a storm is on its way.

Some failures, such as the port jib sheet catching and lifting up the bathroom deck hatch even when it was dogged down tight, should have been discovered during a shakedown cruise. All too often such cruises are little more than fair weather sails of limited duration. That's not unexpected, it's human nature at work. It's the rare person who goes looking for poor weather in which to go to sea. Unfortunately, fair weather and short trips won't reveal problems that will only occur under worse conditions or extended cruises. The leaks as a result of water on deck are another example of this sort of problem that can be discovered and cured with a properly challenging shakedown. As Rowe noted, these were not conditions he'd ever experienced before with PANDA, but it is one that could almost be guaranteed on a trans-Pacific cruise, and one that often shows up such deficiencies. Rowe noted, "the obvious things such a leaky deck to hull joint, leaky ports, etc, ... should have been looked at much harder."

What about the steering failure? Rowe commented, "The steering failure was what turned out to be the last straw and was something I should have been better prepared to deal with." He went on later to note, "steering via the emergency steering rudder (the aluminum tube which broke in half during the tow back to port) is very difficult. Although in great physical shape, Jeff was getting tired after 30 minutes of steering."

What about the steering failure? Rowe commented, "The steering failure was what turned out to be the last straw and was something I should have been better prepared to deal with." He went on later to note, "steering via the emergency steering rudder (the aluminum tube which broke in half during the tow back to port) is very difficult. Although in great physical shape, Jeff was getting tired after 30 minutes of steering."

How many sailors have actually tested their emergency steering gear, let alone in challenging conditions? Most emergency gear has limitations that you will be better able to deal with or that you can address beforehand if you have used the equipment prior to the emergency. Don't allow your "last chance" gear to surprise you in an emergency. Know how to use it, know its limitations, and if possible, work out ahead of time a solution to any deficiencies. In this example, an emergency tiller can generally be rigged to take advantage of winches or some line and pulleys and the like to ease the physical burden. It's lots easier if you are set up and prepared to do so ahead of time.

When buying a boat (or any other mechanical or electrical equipment for that matter) it is always a good idea to check with the manufacturer to see if there have been any recalls or recommended upgrades. It is also important to ensure you are listed as the owner so that you will receive notification of any future actions regarding the product. That's the real reason you want to fill out and return those warranty cards. You don't need to provide them requested demographic data, but you do want to be able to be notified in case of a recall.

When buying a boat (or any other mechanical or electrical equipment for that matter) it is always a good idea to check with the manufacturer to see if there have been any recalls or recommended upgrades. It is also important to ensure you are listed as the owner so that you will receive notification of any future actions regarding the product. That's the real reason you want to fill out and return those warranty cards. You don't need to provide them requested demographic data, but you do want to be able to be notified in case of a recall.

Such a precaution might have prevented Rowe's steering failure altogether, as he discovered later, "in 1984, the year PANDA was built, Catalina Yachts came out with a retrofit bracket to reinforce the support for the steering bracket itself. I assume they must have realized that their original configuration as well as thickness of the aft bulkhead to which the steering bracket is attached was inadequate. They say their records show that this retrofit was sent out to the owner of record. Unfortunately, it was never installed. Subsequent Catalina yachts which are newer and even those und er 36' have an aft bulkhead twice the thickness of mine and are equipped with the same steering mechanism."

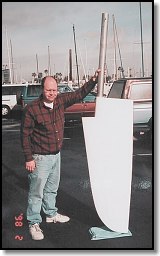

Rowe's preparations for possible deployment of the raft went far beyond that of many life raft owners, for which he is to be commended. "When the raft was checked out at a facility in Wilmington, California, I was present as the raft was removed from the canister and inflated. All items were removed from the raft and I took photos so other crewmembers could see what we had and how it all looked. Prior to departure, all crewmembers were briefed on how to deploy the raft and what they could expect when this was accomplished. However, when it came to using the raft under actual rescue conditions, we were all neophytes."

Rowe's preparations for possible deployment of the raft went far beyond that of many life raft owners, for which he is to be commended. "When the raft was checked out at a facility in Wilmington, California, I was present as the raft was removed from the canister and inflated. All items were removed from the raft and I took photos so other crewmembers could see what we had and how it all looked. Prior to departure, all crewmembers were briefed on how to deploy the raft and what they could expect when this was accomplished. However, when it came to using the raft under actual rescue conditions, we were all neophytes."

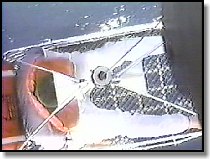

Despite these efforts, entering the raft presented a formidable challenge. Whatever information was gleaned during the servicing of the raft, how to open the door from the water, a critical bit of information, was apparently not covered. There is a provided means to open the raft door from the water (images at right and below are from the 6-person Givens raft we tested in 2000, all Givens entries are nearly identical), however the placard noting this is small, off to the side and not very noticeable among the profusion of placards at the entry to the raft. When you consider the size and conspicuousness of the instructions printed upon the door itself, actually only aimed at those entering directly from the vessel where it is expected someone could literally jump through the door, it's not at all surprising that the survivors didn't notice it.

This line might also prove difficult to use in frigid conditions with cold hands and the Velcro securing the line end could be saturated with water and quickly freeze in very cold conditions.

This line might also prove difficult to use in frigid conditions with cold hands and the Velcro securing the line end could be saturated with water and quickly freeze in very cold conditions.

Rowe commented, "We later learned there is a line on the side of the door that when pulled will open the door. None of us has any recollection of ever noticing such a line. I did read the manual for the raft; I suppose an explanation is in there someplace." The Given's raft manual does not, in fact, contain such information. Besides, that manual is located inside the raft, you have to open the door to get at it, so it would be worthless even if it was there, unless you had a chance to review a manual ahead of time, which isn't a bad idea, by the way. Nor is it mentioned in the deployment instructions on the Givens canister. If someone hasn't instructed you in its use, the odds of discovering it on your own during an emergency deployment are slim. Rowe commented, "leaving your vessel and entering a raft under less than optimal conditions is a stressful experience. All items for entering the raft should be clearly marked and readily accessible. We all fault Givens on that one."

The situation with the Givens life raft entry has been noted previously in the ETS/Belvoir Publications life raft evaluations (published in the May, June and July issues of Practical Sailor and Powerboat Reports and it will be expounded upon further in our upcoming ETS review). This real life experience simply validates our findings that the closed entry upon deployment presents a potentially formidable barrier, not only visually, but also physically, particularly for entry from the water where a survivor is unlikely to notice the alternate means of opening the door.

We noted also that the entry aids were inadequate and that one volunteer tester was unable to board the raft. We concluded that the Givens raft is far too difficult to enter from the water, potentially impossible, and this experience also bears this out.

We noted also that the entry aids were inadequate and that one volunteer tester was unable to board the raft. We concluded that the Givens raft is far too difficult to enter from the water, potentially impossible, and this experience also bears this out.

Rowe remarked, "the so-called boarding ladder was totally useless. This is a cloth affair with about 3 or 4 rungs (Actually only 2 - Ed.)sewn into it. In rough seas it must simply be swirling around. Not one of us was able to find it and help ourselves into the raft. I was the last person to leave PANDA and swim to the raft. Upon arriving at the raft, I deliberately stayed outside in the water and while hanging felt around with my legs searching for the 'ladder.' I was never able to find it. With help, I was pulled and climbed into the raft. Again, we all fault Givens on a worthless boarding ladder."

Note also that the conditions at the time were not extreme and it only serves to punctuate our assessment regarding these deficiencies and their potentially adverse impact in an emergency.

Whenever possible, you want to enter the life raft directly from the vessel. Dryer is better than soaking wet and even the best rafts can be difficult to enter from the water in extreme conditions. This requires that the raft be brought alongside. However that's not always possible Rowe noted, "Jack mentioned later how hard it was to hold on to the painter to the raft and how difficult it was to pull the raft to within about 30 feet or so of the transom." Rowe went on to explain, "(the raft) opened up as expected but immediately began to drift away very rapidly. As a result of hanging onto the painter as it slipped through his hands, he received rope burns on this palms and fingers. He then went back to the port side of PANDA in the cockpit and wrapped the painter around a primary winch."

PANDA was drifting in bouncing seas at this point and the the raft was acting as a sea anchor. As Jack began to work the winch to pull the raft in closer he noticed that PANDA began rocking back and forth more violently. He was concerned that if he pulled the raft in closer that PANDA would come down on the raft and sink it, so he let more line out in order to keep it away. He got the raft as close to PANDA as he felt he safely could, so we swam to the raft.

With a life raft equipped with good ballast, and the Givens raft with its hemispherical ballast is as well equipped as it gets, there is considerable drag. Most rafts are also equipped with a drogue (also referred to as a "sea anchor") designed to stabilize the raft and slow its drift rate. His difficulty pulling in the raft under those conditions isn't surprising.

If you examine the images of the raft deployment taken from the Coast Guard video, you'll note that the lower portion of the canister (the small white form near the raft) is retained on the painter. This is another less than desireable feature found on many rafts, the Givens included, that we noted in our tests. Anyone swimming to the raft can be injured by this chunk of heavy, somewhat rough-edged fiberglass, and if could even harm the raft itself in some circumstances. It's better if the canister falls away completely after deployment. If your life raft canister has a hole that the painter exits from (as opposed to a slot), keep this in mind if you ever find yourself abandoning ship, so that it doesn't surprise you as you make your way to the raft.

If you examine the images of the raft deployment taken from the Coast Guard video, you'll note that the lower portion of the canister (the small white form near the raft) is retained on the painter. This is another less than desireable feature found on many rafts, the Givens included, that we noted in our tests. Anyone swimming to the raft can be injured by this chunk of heavy, somewhat rough-edged fiberglass, and if could even harm the raft itself in some circumstances. It's better if the canister falls away completely after deployment. If your life raft canister has a hole that the painter exits from (as opposed to a slot), keep this in mind if you ever find yourself abandoning ship, so that it doesn't surprise you as you make your way to the raft.

Just to reiterate a most important point, the painter should always be secured to the vessel before deployment of the raft over the side. That is an absolute. No one can hold onto a raft in even the most moderate conditions.

Most marine rafts have fairly long painters, as Jack discovered. Unless extraordinary conditions warrant it or this is no time to do otherwise, don't simply tie off the end of the painter (or it may be already attached in many installations) and deploy the raft. In most circumstances you will have to pull out the excess length of painter until you reach the end and the raft deploys, as Jack experienced. It may require a sharp jerk on the painter to activate the inflation mechanism if conditions are not extreme and the raft canister or valise isn't being carried away from the boat. When you see a deployment demonstration at a boat show or safety at sea seminar, this is typically how it is done with the demonstrator flailing away as they pull out a seemingly never ending length of painter. All well and good on dry land, but not the best strategy in actual circumstances

If at all possible, use some means, another cleat for example, or a winch, to shorten the painter up as much as possible as you deploy the raft and pull out the painter. It is a lot easier than trying to bring the raft back to the boat. In most circumstances you can expect the deployed raft to quickly be left behind as the boat drifts faster than the raft, witness this incident as typical. Also, as Jack discovered, it helps if you, and all the crew, wear gloves. Not only to protect your hands during the deployment, but especially so that you can more easily grasp the painter and the raft's entry aids.

Jack's use of the winch to pull the raft back to the vessel was exactly the right tactic. You are unlikely to be able to drag it closer to the boat by brute strength alone unless conditions are dead calm.

While it is generally recommended that a life raft be deployed off the stern of the vessel, this raft was deployed off the port side of PANDA right next to where the life raft was stored on the deck in its cradle, aft of and to the port side of the mast. Jack explained to Rowe that he had little other choice as he recalled that PANDA was rocking violently to and fro, port to starboard, and that there was no way he was going to carry or somehow move the raft to another position on deck for launching. He also noted that where he launched the raft there was little rigging in the way and he felt that he had a clear shot to get the raft into the water. Something to keep in mind when you select a life raft and its placement on deck. Both the weight and location bear on your ability to launch the raft where you'd prefer, as opposed to where you can.

If you must swim to the raft, it is important to have a secure hold of the painter. In very poor conditions drift could take the raft and boat away from you at a pace faster than you can swim in your clothing and PFD.

Rowe did exactly the right thing sending Jeff out first. Most recreational life rafts are difficult to board. Some are damn near impossible to board. Adverse conditions only make matters worse. It only makes sense for the first person to be the strongest and most capable. Once on board, he or she can then assist others who may have a much more difficult time of it without help. It's much easier to give assistance from inside than it is to try and boost someone on board from the water.

Two tips: One, (assuming the person in the water is wearing a PFD!) after warning them what you're going to do, you can push the person down into the water, then when they bob to the surface continue the upward motion pulling them on board. Two, avoid pulling them on board backwards, despite what you may read or see elsewhere. Humans don't bend in that direction and injury could conceivably result. Have them face the raft with their face turned to the side as you pull them on board. With one person assisting, grab either the PFD straps or under the arms and pull them up and over the raft buoyancy tube(s), falling back yourself and pulling them over on top of you. With two persons to assist, have one on either side, grabbing hold with the interior hand so the person being brought on board comes over between the two of you.

Rowe concluded, "once we were all inside the raft it was cozy, but roomy enough for all of us. As Jack cut the painter attaching us to PANDA and we floated away, I felt secure in the raft. The bottom line is it did perform when needed, but we were lucky to have Jeff aboard to lead the way for the rest of us."

Rowe was lucky that his VHF radio proved adequate to communicate with the Coast Guard. At those distances, it would not have been a reliable means, "had I been thinking, I instead would have used the HF radio. We were off shore about 300 NMi at this point and theoretically VHF is line of sight only. Luckily, VHF worked." Rowe remembers, "initially comms with the Coast Guard were very poor. Then the Coast Guard operator changed some operating parameters (switched antennas or rotated the antenna) and comms were greatly improved. Thank goodness for tropospheric ducting!"

Rowe was lucky that his VHF radio proved adequate to communicate with the Coast Guard. At those distances, it would not have been a reliable means, "had I been thinking, I instead would have used the HF radio. We were off shore about 300 NMi at this point and theoretically VHF is line of sight only. Luckily, VHF worked." Rowe remembers, "initially comms with the Coast Guard were very poor. Then the Coast Guard operator changed some operating parameters (switched antennas or rotated the antenna) and comms were greatly improved. Thank goodness for tropospheric ducting!"

The HF failure wasn't the sort that might normally have been forseen, but its likely cause might encourage you to take a closer look at your set up. "The connection of the microphone jack to the HF radio was solid prior to departure...I called home using the Icom M-710 HF rig via KMI in San Francisco...I suspect that one of the crew accidentally leaned against or backed into the face of the HF radio and unknowingly snapped off the 8-pin jack going from the microphone cable to the radio."

Rowe has learned his lesson the hard way, luckily with nothing lost, "I have now installed a protective bar across the face of the radio to prevent this from happening again. Additionally, I now carry a spare microphone in a vacuum-sealed bag aboard PANDA. This $90 investment is worthwhile for the peace of mind it brings." Murphy is an ever present stowaway aboard all vessels. If something critical can be broken off a device, you can bet that sooner or later it will happen; something to consider as you organize your equipment installation.

Many electronic devices have peculiarities that aren't apparent initially. Rowe continued, "When I noticed that the mike was broken off the HF radio, I knew we were not going to be transmitting. I never suspected that this would also prevent us from receiving as well." While most of us tend to give short shrift to instruction manuals, if your life may depend upon a device it is well worth the time and effort to thoroughly review the entire manual. Sometimes important information is buried in places you might not normally look. The listed specifications often contain such hidden information.

Many electronic devices have peculiarities that aren't apparent initially. Rowe continued, "When I noticed that the mike was broken off the HF radio, I knew we were not going to be transmitting. I never suspected that this would also prevent us from receiving as well." While most of us tend to give short shrift to instruction manuals, if your life may depend upon a device it is well worth the time and effort to thoroughly review the entire manual. Sometimes important information is buried in places you might not normally look. The listed specifications often contain such hidden information.

The question of what spares to carry bedevils anyone who sets out on an adventure, no matter the means of transport. You simply cannot carry spares for everything. We balance what we carry with the potential ultimate cost of not having a spare when we need it, and often the price of the spare itself enters into the equation. Experience is your only guide, both your own experience and that of others who have made similar trips or used similar equipment. Some manufacturers have recommended spares they suggest you carry, lists developed from experience. Unfortunately, such companies are relatively scarce, few like to admit their products can fail. With the Internet, finding others with experience has become immeasurably easier, albeit it generally requires a significant investment in time and effort--well worth it in my opinion.

I should also make note that any spares you carry must be protected from the elements, as in the example of Rowe vacuum packing his spare microphone, and many have limited shelf life. Seals and such made of rubber, as well as many adhesives, tend to have limited shelf lives.

Sometimes it isn't easy to abandon a long sought after goal in which you have a lot invested, both financially and emotionally (such as sailing to Hawaii). There is sometimes a fine line between what's doable, and prudent, and what is carrying things too far. Even with the Coast Guard's advice to return immediately to port because of Jacks' medical condition, some discussion ensued and Jack was reluctant to give up.

As for Jack's condition, was it prudent to continue in the first place in light of such serious seasickness? What about once he started complaining about chest pains? Many have been violently seasick at the start of a cruise; it's not much concern unless it continues unabated for a number of days. Having said that, if the scopolamine patch wasn't effective initially, it is unlikely to do better later on. Oral medication at this point was futile. Not only is the patient unlikely to keep it down, as was the case, but traditional anti-emetics are virtually useless after the fact. Without some signs of improvement within a couple days, you'd need to seriously question continuing the journey.

However, chest pain of any kind is potentially serious, even more so in older individuals. I'd be inclined to suggest that absent some other mitigating circumstances, it would be prudent to immediately contact medical assistance for consultation.

Finally, with regards the seasickness issue, it's not a bad idea to have some more powerful medications that don't require consumption available in case of an emergency. Remarking on the anti-emetic situation, Rowe noted, "My medical bag now contains phenergran suppositories for this very reason." Also, there are alternative treatments that many find effective, in many cases even after the nausea begins. Some of these don't require consumption either, making them particularly appropriate under such circumstances. They may be worth having aboard, just in case. Anyone can become seasick--anyone!

Commenting upon the medical kit, Rowe wrote, "I purchased this kit for about $500 from Seaside Marine in San Pedro, California. A prescription from my physician was required. Seaside has a reputation for building these kits for offshore sailors and was recommended by an instructor at Orange Coast College during an Offshore Medical Course we took about a year prior to departure."

Commenting upon the medical kit, Rowe wrote, "I purchased this kit for about $500 from Seaside Marine in San Pedro, California. A prescription from my physician was required. Seaside has a reputation for building these kits for offshore sailors and was recommended by an instructor at Orange Coast College during an Offshore Medical Course we took about a year prior to departure."

Despite the expense, Rowe feels that some medical priorities may not have been appropriately considered, "what I found so very disappointing and upsetting about this expensive investment was that for the most common malady at sea, seasickness, all they had to offer was a single bottle of little blue pills. For far less common maladies, there was all kinds of equipment for suturing, cutting, etc. I called Seaside several weeks after our return and expressed to the pharmacist my great dissatisfaction with their product. He did say they would add Phenergren to the kit in the future." A check of their Web site shows that they now include Trimethobenzamide 200mg Suppositories (Tigan), which is a similar antiemetic.

A similar situation arose as both sea conditions and the boat's condition deteriorated. While Rowe wasn't yet prepared to abandon ship, the Coast Guard obviously recognized that the snowball was starting downhill. We are lucky that despite serious financial difficulties caused by ill-advised cutbacks and heaping on of added duties, they still have the wherewithal to act on such gut feelings as a precautionary measure.

Did Rowe make the right decision to abandon ship? Even he has cause to second-guess has decision, "given time, I feel certain we could have jury-rigged some sort of emergency steering. Perhaps I should have had just Jack go back with the Coast Guard and the three of us could have worked something out."

Given that the boat was eventually recovered in essentially sound condition, such Monday morning quarterbacking is inevitable. The bottom line is that it was a prudent judgment at the time given the circumstances.

Lives come before equipment. You carry insurance at least in part so making a decision such as this is easier. If you're going bare, without coverage, it's far more difficult to take such action in all but the most seriously perilous circumstances, and then it may be too late.

Still, few could fault a decision to stay under such circumstances. There is an old saw that became popular after the tragic 1979 Fastnet yacht race where numerous abandoned yachts were later found intact and some lives lost after abandonment, "step up into your life raft." The point is to suggest that you shouldn't normally abandon ship until the boat is actually sinking underneath your feet (an out of control fire on board being the most likely exception). Many boats have survived after a premature abandonment.

![]() The boat was still afloat and steerable and was taking on only fairly small quantities of water, it was not gushing in by way of a hole below the waterline. A gas driven pump could have been dropped by the Coast Guard to alleviate the need to manually pump out the incoming water. With that taken care of, forecast conditions, while uncomfortable, were unlikely to threaten the boat if the steering situation was resolved or, at least, mitigated. However, even a complete steering failure wouldn't necessarily doom the boat in forecast conditions, the boat survived no one at the tiller, after all. Finally, they were equipped with a 406 EPIRB and a better quality life raft that despite its deficiencies was certainly capable of saving their lives in forecast conditions once they boarded it.

The boat was still afloat and steerable and was taking on only fairly small quantities of water, it was not gushing in by way of a hole below the waterline. A gas driven pump could have been dropped by the Coast Guard to alleviate the need to manually pump out the incoming water. With that taken care of, forecast conditions, while uncomfortable, were unlikely to threaten the boat if the steering situation was resolved or, at least, mitigated. However, even a complete steering failure wouldn't necessarily doom the boat in forecast conditions, the boat survived no one at the tiller, after all. Finally, they were equipped with a 406 EPIRB and a better quality life raft that despite its deficiencies was certainly capable of saving their lives in forecast conditions once they boarded it.

Please note that I'm not suggesting that they should have continued on to Hawaii had they just disembarked Jack. At a certain point you have to admit that problems are piling up, you're merely a couple hundred miles offshore and there's a long, long way to go in a vessel that's already not so subtly letting you know she's not really as prepared for the adventure as believed. There are situations where you have few choices other than to continue on. This was certainly not one of them.

As Rowe concluded, "Most all of the issues that faced us were troublesome, but only one or two would have stopped us from reaching our goal." It only takes one. It often takes more courage to turn back than to continue.

|

| SELECT AND USE OUTDOORS AND SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT, SUPPLIES AND TECHNIQUES AT YOUR OWN RISK. Please review the full WARNING & DISCLAIMER about information on this site. |

Story by Arnold Rowe

Publisher and Editor: Doug Ritter

Email: Doug Ritter

URL:

http://www.equipped.org/0600rescue.htm

First Published: April 17, 2001

Revision: 02 April 6, 2006

![]()

Email to: [email protected]

|

Story © 1998 Arnold Rowe - All rights reserved. © 2001 Douglas S. Ritter & Equipped To Survive Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. Check our Copyright Information page for additional information. |

Read the ETS Privacy Policy |