|

|

AOPA Pilot Takes Punitive Action Against ETS Editor On September 13, 1999, I was informed that an existing assignment for a safety related feature article I was to do this Winter for AOPA Pilot had been withdrawn. This punitive action is a direct result of my efforts to correct the errors in Tom Horne's ditching article after they declined to do so. It appears AOPA Pilot is more concerned about its bruised ego than its readers' safety. For the latest exchange between AOPA Pilot and Doug Ritter, see below. |

The July, 1999, issue of AOPA Pilot magazine featured an article by Editor at Large Thomas A. Horne titled, "In-Flight Emergencies - Ditching - Putting wings in the water." While we commend the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association and AOPA Pilot for publishing a piece on ditching, Horne's article is a disaster. Though it includes much valuable information on ditching and water survival, it is also chock full of old wives' tales and just plain factually incorrect information. The result is not only grossly misleading, but could, and apparently has dissuaded some pilots from properly preparing for a possible ditching.

The July, 1999, issue of AOPA Pilot magazine featured an article by Editor at Large Thomas A. Horne titled, "In-Flight Emergencies - Ditching - Putting wings in the water." While we commend the Aircraft Owners and Pilots Association and AOPA Pilot for publishing a piece on ditching, Horne's article is a disaster. Though it includes much valuable information on ditching and water survival, it is also chock full of old wives' tales and just plain factually incorrect information. The result is not only grossly misleading, but could, and apparently has dissuaded some pilots from properly preparing for a possible ditching.

Anyone who has been in journalism for long, including your humble editor, has had the embarrassment of being caught short and having to own up to such an error. A minor error is often corrected via a published correction in an appropriate or established location or via a published response to a letter to the editor. A serious error calls for much more noticeable efforts unlikely to be overlooked. In the case where an error could have life or death consequences, a full correction or retraction, as appropriate, equal in visibility to the original, is generally the solution. We believe that in matters of safety and survival, serious errors are potentially life threatening and should be treated as such.

After nearly two months' of correspondence and conversation between us and also with others who have shared with me their correspondence and conversations, it is apparent that Horne is not going to respond or publish a correction in AOPA Pilot, regardless of how many pilots may be misinformed or the potential adverse impact that misinformation may have for the cause of aviation safety. Considering that AOPA serves over 350,000 members, well over half of all U.S. pilots, that's a lot of misinformation. Because the article is also archived on the AOPA Web site and in AOPA's library and will be sent to any AOPA member requesting information on ditching or preparing for over water flight, that also means that the article will continue to do damage for years to come.

For an editor of Horne's stature and a publication held in such high regard as is AOPA Pilot (which I am proud to have contributed to on occasion), that is unfortunate. Except for an edited-down version of my original letter-to-the-editor published in the September issue, which only discuss the most horrendous of the errors, that's the end of it as far as Horne and his boss, AOPA Pilot editor Tom Haines, is concerned. Not so for us.

| On September 7, 1999, a revised version of Tom Horne's article replaced the original on the AOPA Pilot Web site. This revised version corrects the most egregious errors and omissions of the original, though not all in our opinion. Click here to view both versions of the article. On September 16, 1999, I was advised that there would be a notice in the "Letters" section of AOPA Pilot's October issue, along with another letter to the editor. (An unedited vesion of which is available here, see below for details.) |

Where safety and survival is concerned, we feel that it is paramount that the information presented be as accurate as possible. It's difficult to imagine a pilot who might disagree. Correct information is essential when dealing with anything that could impact a pilot's safety. Presenting such information generally requires a high degree of familiarity with the subject, which Horne appears not to have, or good research. All Horne needed to do in order to get many of his facts correct was to walk down the hall to the AOPA Air Safety Foundation. The AOPA ASF Emil Buehler Center for Aviation Safety Database (containing the full information from tens of thousands of NTSB reports on general aviation accidents) could have easily provided many of the answers, if he had asked. As editor, it is Haines' responsibility to assure the articles have been researched properly and to fact check them if indicated. Ultimately, Haines is responsible for all the editorial content of the magazine.

Where safety and survival is concerned, we feel that it is paramount that the information presented be as accurate as possible. It's difficult to imagine a pilot who might disagree. Correct information is essential when dealing with anything that could impact a pilot's safety. Presenting such information generally requires a high degree of familiarity with the subject, which Horne appears not to have, or good research. All Horne needed to do in order to get many of his facts correct was to walk down the hall to the AOPA Air Safety Foundation. The AOPA ASF Emil Buehler Center for Aviation Safety Database (containing the full information from tens of thousands of NTSB reports on general aviation accidents) could have easily provided many of the answers, if he had asked. As editor, it is Haines' responsibility to assure the articles have been researched properly and to fact check them if indicated. Ultimately, Haines is responsible for all the editorial content of the magazine.

In the following commentary and in a supporting article from Aviation Safety magazine by respected aviation editor Paul Bertorelli, "Ditching Myths Torpedoed!," we hope to at least start turning the tide on the sea of misinformation propagated by Horne.

It may also be informative to read the following:

| UPDATE Sept. 21, 1999: An edited version of Greg Marshall's letter (above) has been published in the "Letters" section of the October, 1999 issue of AOPA Pilot. (Read the unedited version here.) The letter is followed by statistics covering 1983-1999 of "143 ditchings, 20 of which resulted in fatalities. Most of these fatalities occurred after ditching in cold ocean waters." This is followed with an admission that "our statement that 'most ditchings are unsuccessful'... was in error." The total quantity of ditchings does not jibe with either my own or Paul Bertorelli's numbers, but the fatality rate isn't too far off. They go on to say "This and other issues raised by readers concerned about ditching information have been addressed in changes to the ditching article on AOPA Online..." As noted above, we don't believe all the issues raised have been addressed. Nor do we feel that the letters-to-the-editor section is an appropriate place for announcing substantive corrections dealing with serious safety matters. Finally, those corrections are not accessible to a significant number of AOPA members who do not have online capabilities.

UPDATE October 10, 1999: After a phone conversation with AOPA Editor Tom Haines and after reviewing the October issue, I responded with an email to Haines, copied to AOPA President Phil Boyer. Haines replied. You can read this exchange of emails, along with my analysis of Haines' reply. The bottom line remains that AOPA Pilot does not put the safety of its readers first. |

The most significant failings in Horne's article involve his statements about the odds for surviving a ditching. Horne repeats a number of old wives' tales in this regard that are not supported by any evidence of which I am aware. Some of his conclusions differ significantly from my findings and experience collected over a decade of research on aviation safety and survival issues, as well as that of associates in this field. As such, I was curious what sources Horne used as the basis for the following statements:

The most significant failings in Horne's article involve his statements about the odds for surviving a ditching. Horne repeats a number of old wives' tales in this regard that are not supported by any evidence of which I am aware. Some of his conclusions differ significantly from my findings and experience collected over a decade of research on aviation safety and survival issues, as well as that of associates in this field. As such, I was curious what sources Horne used as the basis for the following statements:

"Unfortunately, most ditchings are unsuccessful. Even with help close at hand, airplanes often skip once, then flip over or plow under before anyone aboard has a chance to escape."and

"If luck is with you, the airplane stays upright and no one is injured to the point of incapacitation. If it isn't, the airplane is hit by a wave and sinks immediately."

If by "unsuccessful," one meant that the airplane can't be used again, that's probably true. On the other hand, I cannot conceive how Horne could interpret the readily available facts to conclude that the majority of ditchings are unsuccessful, by which I can only infer from the substance of the article that Horne means they result in a fatality or fatalities due to the failure of the occupants to exit the aircraft. Even a cursory review of NTSB or USCG records will reveal that most ditchings are by this measure, or any measure, successful, meaning that the occupants escape from the aircraft reasonably intact or that there are no fatalities.

More specifically, Paul Bertorelli has conducted a review of NTSB accident records in his accompanying Aviation Safety article, "Ditching Myths Torpedoed!". His bottom line on general aviation ditchings: "Although survival rates vary by time of year and water-body type, the overall general aviation ditching survival rate is 88 percent." Moreover, Bertorelli's analysis concludes that "...the successful egress rate is 92 percent, meaning that in more than nine out of 10 cases, at least some of the occupants got out of the airplane and ultimately survived the experience." Bertorelli further reports that "If you exclude what we consider to be the high-risk over water operations--the long distance ocean ferry flights that are only a small part of the total over water flying--the egress rate rises to an astonishing 95 percent."

Bertorelli's numbers are in close agreement with my own research of NTSB and USCG ditching reports. No matter how you play with the numbers or what fudge factor you might add to cover unreported ditchings, you are unlikely to adversely impact the results to any significant degree, and certainly not to the degree necessary to support Horne's statement, given the known facts.

In response to my letter to AOPA's editor, Horne wrote me:

In response to my letter to AOPA's editor, Horne wrote me:

"My intention was to educate pilots on all the risks they face when confronting a ditching, not to reassure them that it is a safe procedure with a single-digit risk of injury. Based on my experience flying over water (North Atlantic, mainly) I know that about five airplanes a year go down in the North Atlantic and the results are invariably fatal. Perhaps your numbers are based on ditchings in warm-water, no-waves conditions."

Whatever Horne's intention, the actual result was far different, a result all too evident at EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 1999 where I presented a Ditching and Water Survival seminar (with Horne and his wife sitting in the third row) and where Winslow LifeRaft Co. had a booth. In a letter to Horne, Gerard Pickhardt, V.P. of Winslow, writes of his experience at the booth discussing with a pilot his interest in a life raft, "I know if I do ditch though, I don't have a chance of surviving." Ergo, why invest in survival gear when the outcome of the ditching is unlikely to be successful?

Pickhardt and his aviation sales representative, Steve Weatherly, both reported numerous conversations similar to this one. I had a few similar ones myself during the course of my stay in Oshkosh and via a variety of online medium over the past couple months. Pickhardt commented that while denial by pilots is always something that must be overcome to sell life rafts, as all of us in the flight safety and survival business know too well (see Barry Schiff's "Safety Is A Tough Sell"), this flurry of abject resignation over the outcome of a ditching is new, manifesting itself just since Horne's article appeared. The bottom line is that the patently false message Horne delivered is actively dissuading pilots from preparing to survive a ditching.

More than just convincing them they don't need survival equipment, it also puts pilots in the worst possible state of mind. A positive state of mind is an individual's most important survival tool. If a pilot is already convinced his chances of surviving are slim, then there is a good chance that reality will conform to his preconceptions. Horne's message isn't just wrong and misleading, it is potentially deadly.

Almost as bothersome, from a philosophical standpoint, is that Horne's chosen method of educating pilots to the supposed risks of ditching is little different than the rampant sensationalism of which that those of us in aviation so often accuse the general media when covering aviation incidents and accidents. Apparently Horne believes it is OK for him to sensationalize the risks of something in order to get a message across (albeit unsuccessfully), while we criticize others for doing just that.

Horne's statements are based solely on his own personal experience with a very narrow range of over water operations. I wonder how many AOPA Pilot readers fly in that rather extreme environment? I would expect it to be a very, very small number. Beyond that, his statement that "the results are invariably fatal" is simply not true. In fact, it isn't even close.

Horne's statements are based solely on his own personal experience with a very narrow range of over water operations. I wonder how many AOPA Pilot readers fly in that rather extreme environment? I would expect it to be a very, very small number. Beyond that, his statement that "the results are invariably fatal" is simply not true. In fact, it isn't even close.

We know of a number of highly publicized instances where pilots ditching in the North Atlantic survived, which immediately gives lie to his statement. Moreover, Bertorelli found, " 22 blue water ditchings...there were four fatalities in this group of 22, for a survival rate of 82 percent, not too much worse than it is for coastal or inshore ditchings."

So, while the survival rate for ditching in high seas and cold water is lower, to take a few such instances as the basis for such an article, which are not representative of the entire universe of ditchings or even of blue water ditchings, and unlikely to be experienced by the vast majority of AOPA Pilot readers, is specious at best and does Horne's readers a disservice.

Horne even addressed the problem of considering ditching only from the perspective of ocean flying:

"Perhaps the problem is that ditching (sometimes given the less-threatening, gentler-sounding 'water landing' moniker) is too commonly thought to be an issue only in transoceanic flying. But that's wrong. An engine failure or other serious problem can crop up over lakes, rivers, bays, or inlets just as easily as it can over dry land."

Yet, presenting it from that narrow perspective is exactly what Horne admits he did. Not that the experience was valid, as noted above, but he contradicted himself in his own article by doing so and never provided that critical bit of information to his readers to put his comments in context.

Our pilot readers are intelligent enough to draw their own conclusions relevant to their own operations given the full and true facts. Our obligation as journalists, in my opinion, is simply to give them the facts they need to make rational decisions and to make reasonable suggestions based upon those facts. Ultimately, they are Pilot In Command and must make the decisions--decisions that should be based on all available information--information that should be correct and complete when provided to them by supposedly reliable sources.

Horne is also just plain wrong when he claims in the article that:

Horne is also just plain wrong when he claims in the article that:

"But if the airplane flips over - as so many high-wing airplanes are wont... Surviving this kind of scenario is much less likely, especially if the seas are high."and

"If it's (the airplane is) upside down, disorientation can make it (egress) almost impossible."

Records concerning whether high-wing aircraft are more likely to flip after impact with the water are not so easy to find; NTSB and USCG records are remarkably silent on this issue, Bertorelli found only one such, though that in itself might be significant. However, one can draw some conclusions from the experiences of the large number of ditching survivors that have been interviewed or about whom news articles have been written. I have personally interviewed many such survivors (or their rescuers) in the past five years, approximately half of whom were flying fixed-gear high-wing aircraft. Only three reported flipping over and completing the water landing upside down, and all survived the experience.

Irrespective of whether the aircraft ends up sunny-side up or sunny-side down, the statistics tell us pilots and passengers generally get out safely. Commenting on the high overall survival rate, Bertorelli notes pointedly, "if every high wing airplane flipped over on impact or cartwheeled end-over-end across the water--highly unlikely, by the way--the occupants still managed to egress successfully." Is it a bit disorienting if the ditched aircraft does end up on its back? No doubt it can be, but that doesn't appear to have any significant impact in the real world of general aviation ditchings. Is training helpful? Sure, it could keep you out of that small percentage of fatals, but is unlikely to make a big dent in the overall stats. Horne's statement is not only false for its extremism, it is also irrelevant and once again, self-defeating for any pilot who believes it.

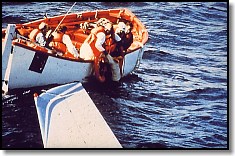

The most common scenario I find is that the aircraft, high or low-wing, fixed gear or retractable, simply noses into the water sometime after initial impact and then bobs back to the surface. All survivors I have spoken with had adequate time to exit the aircraft before the wings sank below the surface. However, there is no doubt from my interviews that those flying low-wing aircraft have it easier getting out and often report time to get organized and retrieve items while standing on the wing and before entering the water or life raft.

There appears to be no data to determine how quickly a particular aircraft will sink. The vast majority report the aircraft sinking shortly after exiting, but some noted the aircraft floating for a considerable time, up to an hour or more in a few cases, days in a few others. In one case I find rather interesting, the quick-thinking survivor clambered onto the rear fuselage of his Mooney and by holding onto the vertical stabilizer, he balanced the aircraft to prevent it nosing over and sinking for long enough to allow for rescue some hours later.

"...ditchings can't be practiced the way we practice "regular" forced landings..."

Why not? A major part of practicing forced landings is not the landing itself, which like a ditching isn't all that different than a normal short and soft field landing, but rather the selection of an appropriate landing spot. While difficult for land-locked pilots, for anyone who plans to fly regularly over water, or who is interested enough to make the effort, it is easily done. A pilot can be instructed, or can practice themselves, how to identify wave and swell patterns, swell and wind direction, and how to prepare the aircraft and any emergency equipment while making a descent towards the water. Doing so will also give lie to Horne's remark that, "You can't really determine the winds, waves, and swell systems until you're at a very low altitude." With practice you can, indeed, do it from higher altitudes than "very low" and do if far more accurately and quickly, no matter what the situation.

This is not significantly different than similar techniques used when practicing normal emergency landings. An added benefit is that after the first attempt to don a life vest under simulated emergency conditions from low altitude, the pilot should quickly become convinced of the need to wear a life vest at all times when flying over water. Preparations for ditchings can and should be practiced.

"As for the prospect of a night ditching, or a ditching in instrument meteorological conditions, well, good luck. That's why many pilots won't even consider a water crossing at night or on instruments..."

"Good luck" is pretty poor advice, particularly since there is no evidence that night or IMC ditchings are generally unsurvivable or even unsurvivable in a significant minority of cases. Many pilots and passengers have survived night ditchings. While there is no question that such a procedure is more difficult and riskier, and a whole lot more scary, it is also likely far more survivable than an off-airport landing under such conditions on land.

In many circumstances, such as with significant moonlight or light scatter from a city nearby, there is ample light to perform a safe ditching under control at night. In addition, if the ditching is precautionary, such as if the aircraft is running low on fuel and will not be able to make it to land, sometimes there is time for USCG or military assistance to arrive and provide illumination of a landing zone with flares. As for flying over water in IMC, in most cases IMC conditions will not go all the way down to the surface, so there is time to get set up for the water landing. Judgement based on actual circumstances is necessary before deciding whether night or IMC flight over water is inappropriate. Understanding the actual risks is necessary to make such a decision.

Rather than presenting such a defeatist attitude or overstating the risk, it would have been far better for Horne to offer some practical advice, such as the importance of setting up a gentle descent, and if at all possible, a slight nose up attitude until contact is made with the water, since if there is zero visibility the pilot won't know when to flare normally. This is obviously easier with power, but by using the altimeter with a recent barometric setting or a radar altimeter, if so equipped, the pilot can also enter the flare at a judicious altitude and hold that attitude until impact, which would likely be far better than impacting in a nose-down attitude.

"Once the airplane hits, you have no control over what the airplane does next."

"No control" is perhaps a bit too absolute in our opinion. In fact, it is critical that the pilot continues flying the aircraft until it stops, just as in a normal off-airport landing. My interviews with ditching survivors support this concept. This is important because it is quite possible that rather than nose-in, the aircraft may skip off the surface of the water on initial and subsequent impacts. In such instances the pilot must continue to fly and maintain control until the aircraft impacts the water the final time.

"No control" is perhaps a bit too absolute in our opinion. In fact, it is critical that the pilot continues flying the aircraft until it stops, just as in a normal off-airport landing. My interviews with ditching survivors support this concept. This is important because it is quite possible that rather than nose-in, the aircraft may skip off the surface of the water on initial and subsequent impacts. In such instances the pilot must continue to fly and maintain control until the aircraft impacts the water the final time.

While the aircraft generally decelerates and stops in a very short distance, the pilot may still be able to control the roll attitude of the aircraft to a certain extent for a short time after initial impact, especially in high-wing aircraft, and keeping a wingtip from digging into the water until the last possible moment can be a real benefit. The point being that a pilot may well have more control than Horne suggests and it does no good to suggest otherwise, contributing to the pilot's poor attitude towards survival.

In addition to these significant errors, Horne also made a few other incorrect statements or omissions:

"...an exposure suit. These suits are made of neoprene rubber and, except for their loose fit, resemble the dry suits used by scuba divers."

Mr. Horne's apparently uninformed statements about exposure suits might dissuade a pilot from considering one, unless required by regulation, which would be a real shame considering how deadly hypothermia can be. The past five or so years have witnessed a revolution in exposure suit design. There are now numerous comfortable and practical options for pilots that are not made from neoprene closed-cell foam rubber, nor which fit as described.

One increasingly popular concept adopted by the military and now available to the rest of us from companies such as Multifabs and Mustang is a design that looks not much different from a conventional military style flight suit, but which incorporates a GORE-TEX waterproof membrane and waterproof zipper, and in some designs, highly effective insulation or insulated underwear. A hood is rolled under the collar until needed, thermal gloves attached by tethers are in quick-access pockets on the sleeves. Integrated GORE-TEX booties allow use of normal footwear, making flying much easier. These are actually quite comfortable for extended wear, which means they are more likely to be worn when needed.

These type suits are used daily in the North Sea oil fields and elsewhere and are well proven in actual survival episodes. Because the materials aren't inherently buoyant like the closed-cell neoprene foam is (an inflatable life vest is still required) they can't possibly trap someone inside a sinking aircraft. They are also far easier to maneuver in, an advantage inside as well as once egress is completed. In addition, the fabric is less likely to snag or to be torn, both potentially life-threatening problems.

A serious disadvantage of the old-fashioned neoprene exposure suits, as described by Horne, is that they are difficult to fly in if fully donned. Even when worn as suggested, the feet are clunky and make flying awkward.

"The usual practice is to wear it in the airplane, but only up to the waist. This leaves your hands and arms free. With practice, you can learn to wriggle your arms and head into the suit, then zip and snap it shut in a few minutes should the need arise."

Sometimes that doesn't quite work out. On December 19, 1998, off the coast of Nova Scotia the pilot survived the ditching, but because he was unable to complete donning the old-fashioned style immersion suit (worn in the manner recommended in the article) he succumbed to hypothermia after exiting the aircraft. It was determined that he would otherwise have survived.

"Life vests for each passenger are a must."and

"On the way down...,if you aren't already wearing it, don your life vest."

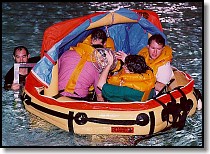

Yes, you do need a vest for every person in the aircraft, and a spare never hurt. However, forget about donning a conventional aviation life vest on your way down to the water, especially so if you're the pilot. Getting into a life vest inside the tight confines of a typical GA aircraft is difficult at best, even for passengers. As pilot, you have lots more important things to attend to. As noted above, a little practice should easily convince you of that. If you're flying over water, wear your life vest at all times. Quick donning pouch style life vests (often called "helicopter vests") are relatively inexpensive and easy to use. Worn at the waist with the pouch sitting in your lap, the vest is simply pulled over the head in an emergency. They are perfect for passengers. Pilots may want to consider a constant-wear vest such as used by the military, USCG, and other experienced overwater pilots, as discussed in-depth in our Aviation Life Vest Reviews article.

Note that conventional aviation life vests are not designed to withstand the abuse of wearing them during flight and have been known to develop leaks very quickly. Typical buoyant marine PFDs or auto-inflating PFDs are dangerous and should never be relied upon as they could trap you in an aircraft (USCG approved manually inflatable marine PFDs are OK).

"...and a handheld transceiver with a built-in GPS will help your chances of being found."then much later in the article

"Seal the transceiver in a plastic bag."

It might have been more responsible to suggest that the radio be kept inside a waterproof pouch specifically designed for the purpose. These are available from the manufacturer in some cases or from most marine supply stores or Web sites such as West Marine at relatively low cost. A simple plastic bag may be better than nothing, but is certainly not the best idea when lives are at stake. They are too easily punctured or inadvertently unsealed, and many are not truly waterproof.

It would also likely be far more economical and result in better com performance to rely upon separate handheld devices for radio and GPS, particularly since most pilots already own both and many GPSes are already waterproof (check your unit's specifications). If not, they make waterproof pouches for GPS units as well, or, small waterproof GPSes are available for under $125.

In addition, don't forget your cell-phone; in many instances it will work better than a VHF radio. You can get waterproof pouches for them as well.

"A small crash axe (the kind with a weighted, pointy end)�With the axe, you can smash out any windows should a door jam and prevent a normal escape."

This is particularly poor and impractical advice for the majority of AOPA Pilot's readers who fly light GA aircraft. As a member of the SAE Aerospace Council, Aircraft Division, S-9 Cabin Safety Provisions and S-9A Subcommittee - Evacuation and Ditching Systems, which just happens to be currently developing standards for Aviation Crash Axes, I am particularly familiar with this subject at this time. The effectiveness of a crash axe in most situations, including that described, is highly variable. One aspect of its use that is incontrovertible, however, is that to be at all effective in the use described by Mr. Horne (which itself is debatable) requires considerable force be delivered by swinging the axe through an arc of some sort, which is highly unlikely within the compact confines of most light GA aircraft cabins or cockpits, especially if the pilot is not alone, and impossible if submerged.

A far more effective and well proven means of opening most GA aircraft doors and fixed windows, and a method widely accepted in the safety and survival industry, is to use both feet to push outward while bracing oneself against some portion of the interior. This has been demonstrated to work on just about any opening or window except in pressurized aircraft, in which case the crash axe is unlikely to be of much use as described anyway.

Horne offers a lot of good advice about life rafts and what constitutes a good raft. Then, he steps right into it again:

Horne offers a lot of good advice about life rafts and what constitutes a good raft. Then, he steps right into it again:

"Expect to pay at least $1,000 for a good raft."

A pilot can barely purchase, new, the worst available life raft for that sum, as our in-depth Aviation Life Raft Reviews article explains. Such a raft will have a single buoyancy chamber with no survival equipment, boarding aids, ballast, or canopy. In essence, it is little more than a self-inflating inner tube with a floor. A "good raft" having the features described by Horne (and you'll get no argument from us about his recommendations) will set you back closer to $2,500, minimum. The result? A pilot searching for a life raft might feel a company like Winslow or BFGoodrich was trying to rip him off when they attempt to sell a good raft, properly equipped, at a reasonable price. As a result he might reject a purchase. Or, he uses Horne's price point as a basis, expecting a quality raft, but gets a poor raft as a result.

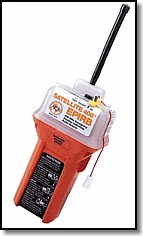

Finally, with regards to signaling equipment, I was particularly distressed that in all his discussion of signaling and survival equipment, Horne never once mentioned the single most highly effective survival signaling device, a 406 MHz emergency beacon. The advantages offered by the 406 MHz beacon are key to a quick rescue. The aircraft's ELT isn't going to be much help once the aircraft submerges.

Finally, with regards to signaling equipment, I was particularly distressed that in all his discussion of signaling and survival equipment, Horne never once mentioned the single most highly effective survival signaling device, a 406 MHz emergency beacon. The advantages offered by the 406 MHz beacon are key to a quick rescue. The aircraft's ELT isn't going to be much help once the aircraft submerges.

There are a number of affordable 406 EPIRBs (the marine equivalent of aviation's ELT) available which will ensure immediate notification of authorities and near instantaneous accurate location of the survivors (unlike 121.5 beacons). These 406 EPIRBs are also available for rent, for those pilots whose need is infrequent. I would urge anyone flying over water to seriously consider adding a 406 EPIRB to his survival equipment. Pocket-size personal 406 MHz beacons are on the way, but there is no reason to wait. It is also worth noting that processing of 121.5 MHz distress signals by COSPAS-SARSAT is going away in the not too distant future.

Failing that, pilots should at least consider a pocket-size personal 121.5 MHz EPIRB. The new Sea Marshall costs only about $130 and could save your life. Not a substitute for a 406 beacon, but much better than nothing and easy to carry at all times.

Another significant piece of signaling equipment that Horne failed to mention is the RescueStreamer, a modern replacement for the short-lived, problematic, and outmoded sea marker dye suggested by Horne. This is a far more effective signaling product, one reason it has been accepted by the military as a replacement for marker dye and also why the U.S. Coast Guard is taking steps to include the RecueStreamer in all their survival vests.

I find all these lapses particularly exasperating considering the many well-attended seminars on Ditching and Water Survival I've given at AOPA Expo (AOPA's annual convention) over the years, including in-water sessions at the past two held in Palm Springs. What are those attendees supposed to think when they see such contradictory information by Horne in the pages of AOPA Pilot? How much of my, and others', efforts over the past few years to educate pilots to the truth about ditching have been negated by this article?

I find all these lapses particularly exasperating considering the many well-attended seminars on Ditching and Water Survival I've given at AOPA Expo (AOPA's annual convention) over the years, including in-water sessions at the past two held in Palm Springs. What are those attendees supposed to think when they see such contradictory information by Horne in the pages of AOPA Pilot? How much of my, and others', efforts over the past few years to educate pilots to the truth about ditching have been negated by this article?

Everyone is entitled to an opinion and if Horne wants to continue to believe that ditching is a risky proposition despite evidence to the contrary, as he writes in one of his letters, "Statistics aside, you have your views and I have mine", he is entitled to do so. However, we draw the line when an editor like Horne allows his opinions to obscure the real facts that pilots need to make up their own minds. Even worse is when an editor like Haines decides to support that position to the detriment of his readers, to whom he is ultimately responsible.

Whatever the cause for the errors in this article, Horne and Haines have a responsibility to both their readers and to AOPA to act in a manner that respects the lives of AOPA members and maintains and promotes the integrity of AOPA.

-- Doug Ritter (AOPA 788447)

For additional information related to this subject on Equipped To Survive™:

|

| SELECT AND USE OUTDOORS AND SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT, SUPPLIES AND TECHNIQUES AT YOUR OWN RISK. Please review the full WARNING & DISCLAIMER about information on this site. |

Publisher and Editor: Doug Ritter

Email: Doug Ritter

URL:

http://www.equipped.org/aopa-ditch-rebut.htm

Revision: 10 November 8, 1999

![]()

Email to: [email protected]

|

© 1999 Douglas S. Ritter & Equipped To Survive Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. Check our Copyright Information page for additional information. |

Read the ETS Privacy Policy |