|

|

It's been an uphill battle against bureaucracies that haven't given a damn about the lives lost by their inaction, but the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has finally approved the sale of 406 MHz Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) in the U.S. Both the U.S. Air Force and the FCC deserve credit for the dubious distinction of holding up Personal Locator Beacon approval for the past few years, and the Federal Aviation Administration must also share some of the blame, but this inertia has at last been overcome. Come July 1, 2003, it will be legal to purchase a 406 MHz Personal Locator Beacon in the U.S., a proven lifesaving device that's been available elsewhere in the world for many years.

It's been an uphill battle against bureaucracies that haven't given a damn about the lives lost by their inaction, but the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) has finally approved the sale of 406 MHz Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs) in the U.S. Both the U.S. Air Force and the FCC deserve credit for the dubious distinction of holding up Personal Locator Beacon approval for the past few years, and the Federal Aviation Administration must also share some of the blame, but this inertia has at last been overcome. Come July 1, 2003, it will be legal to purchase a 406 MHz Personal Locator Beacon in the U.S., a proven lifesaving device that's been available elsewhere in the world for many years.

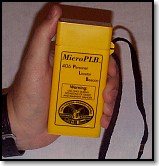

A PLB is a pocket-sized emergency beacon, a scaled down version of the EPIRB (Emergency Position Indicating Radio Beacon) and ELT (Emergency Locator Transmitter) that boaters and pilots, respectively, have had available to them for years. The most easily notable differences are size and cost. PLBs will fit in a pocket, weigh in at about a pound or so and they are expected to sell for prices starting as low as $550 (street price) initially.

| Personal Locator Beacons, also known as PLBs, are finally here and everyone seems to have questions. We've got your answers with the most complete FAQ on PLBs you will find anywhere. Everything you always wanted to know about Personal Locator Beacons (PLBs), including some answers to question you maybe didn't even know to ask. |

With regards to performance, there's really only one significant difference. While the larger beacons must transmit for at least 48 hours at cold temperatures (-40 C), the PLBs are only required to transmit for 24 hours. There are two classes, Class 1 is rated for -40, Class 2 for -20. At warmer temperatures, this is considerably extended. In any case, the primary weight and space savings come from the smaller battery required. It's a fair tradeoff from our perspective to enable you to easily carry such a capable beacon on your person.

The largest Personal Locator Beacon will fit in a coat or cargo pants pocket or in a belt pouch; the smallest PLB is not much larger than a cigarette pack. As with most electronics, there is an inverse relationship between cost and size--smaller is more expensive, at least at this juncture.

The U.S. added two notable requirements to the international Personal Locator Beacon standards. They must include a 25 milliwatt 121.5 analog homing signal. This compares to 100 miliwatt for a conventional 121.5 ELT, 406 MHz ELT or EPIRB or 50 milliwatts for other PLBs. Inserted into the homing signal at the insistence of the FAA is a Morse code P to distinguish a PLB from an ELT.

We have been pushing for this technology for years, being a big proponent of 406 MHz distress beacons because they are simply so much better. A 406 Personal Locator Beacon is just that much more valuable becuase it is small enough for anyone to carry one on their person where it will do the most good. While this approval required the effort of many caring individuals inside and outside government to overcome the bureaucratic deadlocks, a significant amount of credit for this should be given to Lieutenant Commander Paul Steward, the U.S. Coast Guard's COSPAS-SARSAT Liaison Officer (now retired), who had made it his personal quest. His dogged determination and persistence in finding solutions to every stupid roadblock along the way is much admired and appreciated by those of us who have seen him plug away at this for years.

It also required courageous action on the part of a new commander of the Air Force Rescue Coordination Center (AFRCC), Lieutenant Colonel Scott Morgan, who decided that saving lives was, indeed, the business they were in. His personal efforts reversed the Air Force's longtime asinine, small minded opposition to PLBs, removing one of the most significant roadblocks to approval. Anyone with military experience knows what it takes for someone in the military to reverse its existing course, no matter how bad that course was.

Aimed at hikers, backpackers, horsemen, climbers, rafters, kayakers, sailors, hunters, pilots and others who find themselves lost, stranded, injured, or otherwise in need of rescue, Personal Locator Beacons use the same COSPAS-SARSAT satellite notification system as their bigger brothers. Each PLB must be registered, at no cost, with NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration) who maintain the database for 406 MHz emergency beacons in the U.S. Each PLB has a unique digital code, so search and rescue will be able to immediately know who owns the beacon.

On August 22, 2003, NOAA opened up their online 406 MHz beacon registration system, making it even easier to register.

By checking the phone numbers provided when the Personal Locator Beacon is registered, this cuts down dramatically on false alerts and wasted resources. It can also allow authorities to more quickly launch SAR assets when they are able to confirm the likelihood that it is a real alert and the general or specific location even before a location is received from the LEO satellites.

For a comparison between the older 121.5 MHz distress beacons (ELT and EPIRB) and the better 406 MHz distress beacons (ELT, EPIRB and PLB), check out this comparison chart.

The high false alert rate of 121.5 MHz beacons is one of the reasons that satellite notification of 121.5 MHz alerts are being phased out in the near future, and for good reason in our opinion.

The high false alert rate of 121.5 MHz beacons is one of the reasons that satellite notification of 121.5 MHz alerts are being phased out in the near future, and for good reason in our opinion.

Cell phones just won't work in many areas and PLBs provide the most reliable means for someone in trouble in the back country to call for help. You must also have some means of providing the person on the other end of the cell phone call with a location in order for it to be of value, and that's not always possible, especially for those seeking help because they are lost. Cell phones are also not waterproof, have limited battery life and are not nearly as abuse resistant as PLBs.

Major Allan Knox of the AFRCC presented preliminary results at this year's NASAR Conference of a study comparing PLBs to cell phones in attempts to communicate from wilderness areas throughout the U.S. These results show that PLBs definitely hold an advantage over the phones in many circumstances. In approximately 34% of the tests it proved impossible to make contact via cell phone, and these were in areas where there supposedly was cell coverage as shown on phone company maps, and not even particularly remote locations or difficult terrain.

The PLBs will be sold by outdoor sports, marine and aviation suppliers. It is also expected that some outdoor outfitters, boating chandleries and organizations, and aviation suppliers. Companies and organizations that rent beacons will be required to maintain a 24-hour contact number and to have the customer contact information normally required when registering a beacon available for Search and Rescue authorities when they call, if a PLB alert is received.

A test program conducted in Alaska since 1994 has about 400 persons saved to its credit with 378 PLBs registered (many are rentals/loaners used by multiple persons). In 2002 there were 27 rescued in 18 events. Worldwide, where the PLBs have been available for years, numerous rescues have resulted from PLB use. "It takes the search out of search and rescue," said Paul Burke, who helped set up the Alaska test program and directed it for a decade, also speaking at the NASAR Conference. It's a phrase that is used widely by those promoting 406 MHz beacon technology and perfect for describing the advantage offered by PLBs.

The PLB transmits on two frequencies. A digital alert on 406 MHz is picked up by low earth orbiting (LEO) satellites that can determine a location using doppler shift technology. The initial alert is received within minutes in many areas of the world via geostationary satellites, which for the most part cover from 70° North to 70° South latitudes. Location information within three miles and often much better can be determined by LEO satellite passes, taking anywhere from a few minutes to a maximum of an hour and 30 minutes. Within the continental U.S., most users can expect their location will be determined within 30 minutes.

In addition, a traditional 121.5 MHz homing signal serves to guide rescuers to the precise spot using existing homing gear used by most SAR services. Some PLB models incorporate a GPS chip or can be hooked up to a regular GPS receiver to provide location to within a couple hundred feet, providing an accurate alert within a few minutes and almost instant deployment of SAR resources.

The delay until July 1 is to provide the Air Force and state and local SAR systems to coordinate a nationwide rescue system for dealing with this new technology.

The following companies are selling PLBs in the U.S. market:

The following companies manufacture PLBs, but they are not yet available for sale in the U.S.:Click here to view a chart listing currently available PLBs along with their primary features.

There are no penalties for accidental false alerts from a PLB, but deliberate misuse or hoaxes are a federal felony punishable by a $250,000 fine, imprisonment for six years and anyone guilty would also be responsible for paying the cost of rescue.

There are no penalties for accidental false alerts from a PLB, but deliberate misuse or hoaxes are a federal felony punishable by a $250,000 fine, imprisonment for six years and anyone guilty would also be responsible for paying the cost of rescue.

You can review the FCC Order authorizing 406 MHz PLBs including detailed requirements. (Adobe PDF format document).

Get Free Acrobat

(PDF file) Reader

Click here for more information on the COSPAS-SARSAT system and how it works.

Click here to find out more about NOAA's online 406 MHz beacon registration.

Click here for information on ACR Electronics second generation PLBs.

|

| SELECT AND USE OUTDOORS AND SURVIVAL EQUIPMENT, SUPPLIES AND TECHNIQUES AT YOUR OWN RISK. Please review the full WARNING & DISCLAIMER about information on this site. |

Publisher and Editor: Doug Ritter

Email: Doug Ritter

URL:

http://www.equipped.org/plb_legal.htm

First Published: October 18, 2002

Revision: 07 January 7, 2004

![]()

Email to: [email protected]

|