|

|

I have occasionally been asked to assist in selecting survival equipment for a variety of adventures. Typically, all the client wants is a list and a few suggestions for sources. In most cases, they modify a commercially available survival kit and/or get assistance from a company such as Exploration Products. Occasionally it gets more complicated and involved because the one-size-fits-most solution just isn't appropriate. Most commonly I am queried on the matter from six months to a year ahead of time, sometimes even more.

I have occasionally been asked to assist in selecting survival equipment for a variety of adventures. Typically, all the client wants is a list and a few suggestions for sources. In most cases, they modify a commercially available survival kit and/or get assistance from a company such as Exploration Products. Occasionally it gets more complicated and involved because the one-size-fits-most solution just isn't appropriate. Most commonly I am queried on the matter from six months to a year ahead of time, sometimes even more.

In late January of 2001 I was contacted by Simon T (yes, just T) who had entered the London (U.K.) to Sydney (Australia) Air Race. He wasn't just looking for advice or resources, he needed it all put together for him.

Complications stemmed from the fact that Simon was getting a late start, the race was to begin March 11 and he was planning to depart for the U.K. by the end of February. He'd be leaving to fly to his departure airport a few days before that. Moreover, he was planning to fly not a fixed wing aircraft, but rather his Hughes 500C helicopter (registration N7UM and significantly upgraded from original). Weight was a major concern, more so than it normally already is for aircraft. It was such a concern that he'd be flying solo for most of the race, adding to the challenge and the risk and somewhat complicating survival equipment decisions. The route (see illustration below or click for more details) covered a diverse range of environments, from temperate northern to sandy desert, to scrub desert, to subtropical to tropical and a good deal of the flight would be over water.

My first meeting with Simon was on January 29 and I agreed to assist him. That left me no more than 30 days to get it all done, and possibly less. I share here what I did to provide Simon with the survival gear he needed. Not just what equipment and supplies were selected, but why and where required, how we modified them. Hopefully, this will enlighten you to the process and trade offs that such a project entails, making it easier for you to make such decisions when assembling your own survival gear.

That this is serious business and that decisions cannot be made lightly was hammered home just a few days before the race was to begin. Two pilots, flying a Twin Commander from the U.S to the U.K. to participate in the race, lost their lives when they crashed into the icy waters after departing Iceland. Yet, without risk, there's not much adventure. You cannot ever eliminate all risk and the more life you live, the greater the exposure. I view my job as being to mitigate the risks through superior preparation.

That this is serious business and that decisions cannot be made lightly was hammered home just a few days before the race was to begin. Two pilots, flying a Twin Commander from the U.S to the U.K. to participate in the race, lost their lives when they crashed into the icy waters after departing Iceland. Yet, without risk, there's not much adventure. You cannot ever eliminate all risk and the more life you live, the greater the exposure. I view my job as being to mitigate the risks through superior preparation.

NOTE: At the last moment, Simon chose the prudent course and withdrew from the race. After mechanical problems and a marathon 48-hour rebuild of the turbine and gearbox, then a further complication, in the end there just wasn't adequate time to put enough hours on the new engine and gearbox for Simon to feel comfortable flying it half way around the world over potentially treacherous terrain and long over water legs. However, when one door closes, another opens. Simon is already considering other adventures with N7UM. We'll keep you advised.

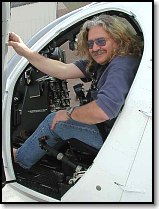

Simon agreed that a constant wear life vest was a must over water, but didn't want to wear a survival vest for flights over dry land. After discussion he settled on a flight suit with extra pockets that I would use for storage of survival gear and supplies. Since that served to restrict how the equipment might be packed, and it needed to be able to be moved from one flight suit to another fairly easily, lets review the flight suit specs we settled on.

Simon agreed that a constant wear life vest was a must over water, but didn't want to wear a survival vest for flights over dry land. After discussion he settled on a flight suit with extra pockets that I would use for storage of survival gear and supplies. Since that served to restrict how the equipment might be packed, and it needed to be able to be moved from one flight suit to another fairly easily, lets review the flight suit specs we settled on.

Flight Suits (formerly known as Flightsuits Ltd.) manufactured the custom made Nomex flight suits; Royal Blue for general use and Khaki for wear over desert areas. We started with their basic Military Style Nomex flight suit with long sleeves. The lower leg pockets and chest pockets were retained, as was the sleeve pocket.

Because Simon is left handed, we moved the sleeve pocket with its pencil holders to his right sleeve and also deleted the cover as an unnecessary bother for our purposes. A second zippered sleeve pocket was added to the left sleeve to hold the MicroPLB. The knife pocket was moved from the left to right inside thigh.

Because Simon is left handed, we moved the sleeve pocket with its pencil holders to his right sleeve and also deleted the cover as an unnecessary bother for our purposes. A second zippered sleeve pocket was added to the left sleeve to hold the MicroPLB. The knife pocket was moved from the left to right inside thigh.

A cargo pocket was added to each leg, replacing the normal thigh pockets. The bulk of the survival gear and supplies would be carried in the leg pockets; water in the lower pockets, the rest in the upper cargo pockets. Front (pants style) pockets were added, but with zippers installed as well for security of their contents in the water. My experience is that in the water King Neptune quickly claims anything in open pockets.

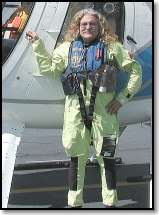

For flights over colder water, across the English Channel and the Mediterranean, a Multifabs Exposure Suit was rented from the U.S. distributor, Concorde AeroSales.

Simon recognized the advantages of modern communications; I didn't need to sell him on the concept. He was already equipped with a pair of Globalstar sat-phones, one mounted in N7UM, but hadn't considered that they wouldn't work if they got wet. We solved that with an Aquapac waterproof case. The Aquapac Large VHF case was the only such case that easily fit the bulky Globalstar phone. That it is one of the best of such products was a convenient advantage. He later added an IMARSAT SatLan phone, primarily for digital communications, including video, for the planned Web site.

Simon recognized the advantages of modern communications; I didn't need to sell him on the concept. He was already equipped with a pair of Globalstar sat-phones, one mounted in N7UM, but hadn't considered that they wouldn't work if they got wet. We solved that with an Aquapac waterproof case. The Aquapac Large VHF case was the only such case that easily fit the bulky Globalstar phone. That it is one of the best of such products was a convenient advantage. He later added an IMARSAT SatLan phone, primarily for digital communications, including video, for the planned Web site.

N7UM was already equipped with a state of the art Artex 406 MHz ELT with nav interface, allowing it to transmit the location in the beacon code. ELTs have mixed effectiveness in the real world,. All sorts of happenstances, including a broken or poorly aligned antenna after the aircraft comes to rest, can affect their performance. In a ditching it would be useless. Simon wanted a 406 EPIRB with integrated GPS for the life raft. The smallest and lightest readily available was Pains Wessex' recently introduced SOS Precision 406 GPS EPIRB, which was procured.

Simon also already wore, as back-up, an "EmergencY" watch, or "wrist device" as Breitling refers to it, that incorporates a low-power 121.5 emergency locator beacon. The supreme advantage of this device is that it's always with you. The disadvantage is that it is not reliably effective for satellite notification and locating purposes.

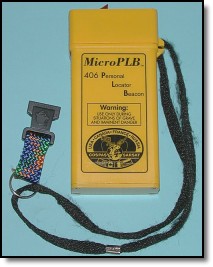

I suggested that a small 406 PLB would be the ultimate back-up and Simon agreed. The difficulty is that it was still illegal at the time to sell a PLB in the U.S., complicated by the fact that the PLB we really wanted, the pocket-sized Microwave Monolithics MicroPLB (1 x 2.25 x 4.75 inches, 7.9 oz.), has not been marketed to the consumer market. To date it's only been sold to government entities. Moreover, all units in production were already spoken for, even if they wanted to (or could legally) sell us one. After further discussions with Microwave Monolithics, however, they generously agreed to lend Simon a refurbished factory production test unit, adding a considerable margin of security to our survival communications arsenal. Because this unit would be moved between the life vest and the flight suit, the easily removed cap was a concern. I added a small piece of tape to secure the cap in place.

I suggested that a small 406 PLB would be the ultimate back-up and Simon agreed. The difficulty is that it was still illegal at the time to sell a PLB in the U.S., complicated by the fact that the PLB we really wanted, the pocket-sized Microwave Monolithics MicroPLB (1 x 2.25 x 4.75 inches, 7.9 oz.), has not been marketed to the consumer market. To date it's only been sold to government entities. Moreover, all units in production were already spoken for, even if they wanted to (or could legally) sell us one. After further discussions with Microwave Monolithics, however, they generously agreed to lend Simon a refurbished factory production test unit, adding a considerable margin of security to our survival communications arsenal. Because this unit would be moved between the life vest and the flight suit, the easily removed cap was a concern. I added a small piece of tape to secure the cap in place.

Simon also carried a compact Yaesu handheld VHF transceiver. It had been set up to plug into the helicopter's communications system, using the aircraft antenna and microphone, as a back-up and for better performance. Since there were approximately 40 aircraft involved in the race, plus the organizers' aircraft, and Simon would be first off every morning, if he went down there would likely soon be aircraft overflying his position.

The bottom line on all this communications gear was that we could realistically expect that if Simon went down, he was not likely going to be missing for long, no matter where he might end up. As my good friends promoting the 406 MHz beacons like to say, we'd "taken the search out of search and rescue." While our preparations had to take into account unforeseen difficulties, and the omnipresent and generally reliable Murphy's Law, by and large we expected that he'd be unlikely to have to spend more than 24 hours before rescue, probably a lot less.

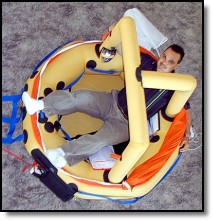

Simon had already purchased a Survival Products life raft, but returned it after reading the Aviation Life Raft Review on ETS. He wanted a more capable life raft like a Winslow. He didn't want, simply couldn't accept, an ounce of extra weight. Winslow LifeRaft Company agreed to custom build Simon a special life raft, modified to reduce weight to a minimum while maintaining substantially all its award winning performance. In selecting the features desired or deleted, we were driven by a few other things besides weight. The race was to be flown only in day VFR conditions. So, a nighttime ditching, seriously high seas and storms were unlikely to be a factor, at least initially.

We figured he might have to wait a while for rescue as some portions of the route were beyond normal helicopter range from shore. That meant he'd have to be picked up by boat, often a much slower proposition. In that time, conditions could worsen and that could delay rescue. So, the raft needed to be capable of surviving for at least a couple days, to provide for a reasonable margin of safety, and to do so in moderately poor weather conditions, but not a typhoon or hurricane.

We also made some compromises to save weight based on the training Simon was to receive, and with knowledge of his size, strength and capabilities. These all can compensate for reduced performance; if you know for sure ahead of time that the user will have the knowledge and is competent to use it.

We started with Winslow's single tube, dual buoyancy chamber GAST "Island Flyer," our top-rated single tube GA life raft, but in a two-person size. The octagonal raft retains Winslow's oversized 13.5-inch buoyancy tube, providing plenty of freeboard. We could have saved more weight by reducing the buoyancy tube size, and could have even met the TSO requirement for a Type II single tube raft with a tube a third or more smaller, but that was too big a compromise to consider if we wanted to maintain the raft's ultimate seaworthiness. The interior comprises 7.2 square feet with a 38-inch diameter interior corner-to-corner measurement.

We started with Winslow's single tube, dual buoyancy chamber GAST "Island Flyer," our top-rated single tube GA life raft, but in a two-person size. The octagonal raft retains Winslow's oversized 13.5-inch buoyancy tube, providing plenty of freeboard. We could have saved more weight by reducing the buoyancy tube size, and could have even met the TSO requirement for a Type II single tube raft with a tube a third or more smaller, but that was too big a compromise to consider if we wanted to maintain the raft's ultimate seaworthiness. The interior comprises 7.2 square feet with a 38-inch diameter interior corner-to-corner measurement.

We settled on a single tube raft instead of a double tube for reasons of weight and in consideration of the limited conditions Simon might likely experience. An inflatable insulated floor was specified partially compensating for the single tube design, once inflated. The floor's topping valve was offset from the center so as not to interfere with the limited space available to Simon.

Small two-person rafts are notorious for being tipsy and unstable. The raft was fitted with three of Winslow's extra deep Cape Horn ballast bags. In testing, I'd found this deep tri-ballast arrangement to be extremely effective on smaller rafts. The ballast retraction lines were deleted to save weight and because we deemed them unlikely to be used in these circumstances. Starting with a 50 ft. long mil-spec parachute cord painter, the minimum length I consider acceptable, equipped with Winslow's standard dual swivels, we upgraded the sea anchor to Winslow's top performing hemispherical parachute drogue for added stability. I'd expect this raft to be very stable in even serious weather conditions, far worse than Simon would likely ever experience.

Winslow agreed to engineer a tri-arch stay-erect canopy for the raft, their first ever for a single tube raft. This provides Simon some extra headroom and space in what would have been a potentially claustrophobically small and restricted enclosed space when the canopy was closed up if the normal single arch canopy has been used. (Bear in mind you don't just throw something new like this together for lifesaving use. A significant change such as this has to be prototyped and tested thoroughly first, all in the limited time we had available.)

Winslow agreed to engineer a tri-arch stay-erect canopy for the raft, their first ever for a single tube raft. This provides Simon some extra headroom and space in what would have been a potentially claustrophobically small and restricted enclosed space when the canopy was closed up if the normal single arch canopy has been used. (Bear in mind you don't just throw something new like this together for lifesaving use. A significant change such as this has to be prototyped and tested thoroughly first, all in the limited time we had available.)

We wanted a pair of Winslow's exclusive viewports in the canopy, but they proved impossible to sew into the ultra light ripstop nylon canopy material that was also specified. Because of the smaller raft size, Winslow was able to reduce the diameter of the canopy arch tubes to 4.5 inches, saving material and weight while still maintaining adequate rigidity to cope with high winds and poor weather. We also deleted the water collection/observation port to save weight. Simon would have other, more reliable means to secure fresh water and on the small raft the canopy opening's double-acting zipper would suffice as an observation port.

Winslow's effective boarding ladder was retained, but the interior boarding assist ladder was changed to one-inch webbing to save weight. Interior grab lines, exterior lifelines and the righting line were all done in one-inch webbing. Simon was equipped with Nomex pilot's gloves or the neoprene gloves of the Multifabs exposure suit, so the narrower lines wouldn't be near the deficiency they might otherwise be. Righting the very small raft is so effortless that with Simon's training there was little benefit to keeping Winslow's otherwise excellent righting aids that normally make a big difference in how easy a raft is to right.

A single storage bag was fitted, made of lightweight sea anchor material, as was the reduced size Survival Equipment Pack storage pouch. We added a two-inch Velcro strip to the back of the SEP and to the buoyancy tube so the SEP could be pulled up off the floor and held out of the way.

All the water activated chemical battery lighting, including the interior light, exterior locator light and the righting light were deleted. Not flying at night, they would not be needed immediately upon deployment. An ACR Electronics Firefly2 Strobe Light with lithium AA-cell batteries was added to the canopy for nighttime location purposes. For an interior light, we used an Essential Gear Guardian single white LED light that is waterproof, extremely light and can be switched on and off. The clip was removed and Velcro was glued to the back of the light with Velcro patches added to the underside of the canopy arch tubes to which it could be attached, moving it around the raft as needed. That proved to work very well, providing brighter and more versatile, longer lasting light than the normal unit fitted. The light can also be used in the hand as a flashlight, if necessary.

All the water activated chemical battery lighting, including the interior light, exterior locator light and the righting light were deleted. Not flying at night, they would not be needed immediately upon deployment. An ACR Electronics Firefly2 Strobe Light with lithium AA-cell batteries was added to the canopy for nighttime location purposes. For an interior light, we used an Essential Gear Guardian single white LED light that is waterproof, extremely light and can be switched on and off. The clip was removed and Velcro was glued to the back of the light with Velcro patches added to the underside of the canopy arch tubes to which it could be attached, moving it around the raft as needed. That proved to work very well, providing brighter and more versatile, longer lasting light than the normal unit fitted. The light can also be used in the hand as a flashlight, if necessary.

The raft is also a potential dry land shelter. Given the environments in which it might be used, we asked Winslow to add nylon No-See-Um mosquito netting as an alternative canopy closure in addition to the regular canopy flaps. Velcro was used to seal the bottom and center with the mesh permanently attached to the canopy at the sides and top.

The raft is also a potential dry land shelter. Given the environments in which it might be used, we asked Winslow to add nylon No-See-Um mosquito netting as an alternative canopy closure in addition to the regular canopy flaps. Velcro was used to seal the bottom and center with the mesh permanently attached to the canopy at the sides and top.

N7UM is not equipped with pop-out floats because of both the added weight and added drag. As such, the helo will turn turtle immediately after being ditched with Simon laying it on its right side to ensure the rotor blades break off behind the cockpit. We have no idea how long it would float, there's significant potential buoyancy beyond that normally available because of the auxiliary fuel tanks which nearly fill the rear passenger compartment--and that varies with how full they may be. However, odds are that it is still unlikely to float for long, we certainly couldn't count on it, though there'd be plenty of time for Simon to get out in any case.

A jettisonable door was initially planned, but time constraints prevented it from being installed. Instead, Simon planned to fly the overwater legs with the right door off, stored in the aft compartment. With moderate weather conditions expected, that was a reasonably viable alternative.

The painter (tether/inflation line) was shortened to just six feet in consideration that this was a solo pilot who would be taking the raft with him when he egressed the upside down chopper. It only needed to be long enough to allow him to board after deploying the raft with the painter clipped to his life vest for security. A lighter weight half-inch webbing was used instead of the regular one-inch webbing and a lightweight plastic clip attached the painter to the boarding ladder instead of Winslow's normal steel D-ring and metal snap clip required to meet TSO retention standards for a normal raft.

In the unlikely case that N7UM did remain floating, Simon could still safely attach the painter to a skid. The lighter weight painter would part before the raft was endangered if the chopper subsequently sank. The raft on the short painter would not be in danger of being struck by the tail as can occur with a fixed wing aircraft.

Winslow's normal construction was retained, with double taped seams using the normal double coated TSO C70a approved neoprene material. The black 16AA material normally used to reinforce attachment points for webbing and such was replaced with a lighter, but more difficult to work with material, still black and equally as strong, but half the weight. This was used as a replacement everywhere except where the canopy arch tubes attached to the buoyancy tube. That difficult juncture required the original material be used. The reeds for the inflatable floor were done in TSO C70a material instead of the normal nylon webbing, again more difficult to work with for production, worth the extra effort in our quest to save weight on this raft.

Winslow's normal construction was retained, with double taped seams using the normal double coated TSO C70a approved neoprene material. The black 16AA material normally used to reinforce attachment points for webbing and such was replaced with a lighter, but more difficult to work with material, still black and equally as strong, but half the weight. This was used as a replacement everywhere except where the canopy arch tubes attached to the buoyancy tube. That difficult juncture required the original material be used. The reeds for the inflatable floor were done in TSO C70a material instead of the normal nylon webbing, again more difficult to work with for production, worth the extra effort in our quest to save weight on this raft.

We deleted all of Winslow's excellent placards, saving not only the weight of the placards, but also the adhesive. A boon to those unfamiliar with using a life raft, it was redundant for Simon with his training, or simply unnecessary on a raft the size of this one.

The heaving/rescue line and raft knife were deleted as unnecessary; the former because Simon was solo, the latter because the short painter wouldn't be connected to the aircraft, so there was no need to cut the painter. Winslow's Quick Grab flashlight was deleted because of the daytime-only flying and because it was redundant to other lights Simon would be carrying on his person. A holster was added for the EPIRB, in case conditions warranted securing it inside the raft. The normal bailer tethered inside the raft was replaced with a Seattle Sports Camp Bowl, a third the weight, but still holding a gallon of water. We adapted it for use as a bailer by removing most of the bowl's interior splash guard, leaving only enough to serve as a handle.

The heaving/rescue line and raft knife were deleted as unnecessary; the former because Simon was solo, the latter because the short painter wouldn't be connected to the aircraft, so there was no need to cut the painter. Winslow's Quick Grab flashlight was deleted because of the daytime-only flying and because it was redundant to other lights Simon would be carrying on his person. A holster was added for the EPIRB, in case conditions warranted securing it inside the raft. The normal bailer tethered inside the raft was replaced with a Seattle Sports Camp Bowl, a third the weight, but still holding a gallon of water. We adapted it for use as a bailer by removing most of the bowl's interior splash guard, leaving only enough to serve as a handle.

Simon would be carrying all his signaling equipment in his life vest, just in case he didn't egress the aircraft with the life raft. So, the Survival Equipment Pack (SEP) focused primarily on gear needed to maintain the raft, or maintain Simon in the raft.

Simon would be carrying all his signaling equipment in his life vest, just in case he didn't egress the aircraft with the life raft. So, the Survival Equipment Pack (SEP) focused primarily on gear needed to maintain the raft, or maintain Simon in the raft.

A pair of three-inch mil-spec raft repair clamps, a pair of pressure relief valve (PRV) plugs and a roll of duct tape serve to maintain the raft's integrity. Winslow's premium spring-loaded manual inflation pump was tethered in the raft.

Normally, the rudimentary paddles that come with a life raft are used as a cutting board for any improvisation that might be necessary. They are much more effective for that use than as paddles. We didn't include paddles because they are even more ineffective with a solo raft occupant. However, I wanted Simon to be able to use his knife safely in the raft. To this end we had fabricated a 5 x 9 inch .032 titanium cutting board. Weighing only a couple ounces, it is impenetrable. After rounding the corners and smoothing the edges with a grinder, some Device Technologies lightweight Spring-Fast grommet provided edging to prevent the thin metal from cutting into the raft material, adding only a couple tenths of an ounce. Winslow added some duct tape to the edge before packing, just to be doubly sure. All up the board weighed in at only 3.35 ounces.

Normally, the rudimentary paddles that come with a life raft are used as a cutting board for any improvisation that might be necessary. They are much more effective for that use than as paddles. We didn't include paddles because they are even more ineffective with a solo raft occupant. However, I wanted Simon to be able to use his knife safely in the raft. To this end we had fabricated a 5 x 9 inch .032 titanium cutting board. Weighing only a couple ounces, it is impenetrable. After rounding the corners and smoothing the edges with a grinder, some Device Technologies lightweight Spring-Fast grommet provided edging to prevent the thin metal from cutting into the raft material, adding only a couple tenths of an ounce. Winslow added some duct tape to the edge before packing, just to be doubly sure. All up the board weighed in at only 3.35 ounces.

With Simon the sole occupant, I felt it even more critical than usual that we take measures to combat seasickness, a virtual sure bet otherwise if the raft needed to be closed up. Since we had no previous experience with Simon to go on, I adopted a two-pronged strategy that incorporated the two most widely effective remedies I am aware of that also, conveniently, generally have no adverse side effects and are generally effective after the nausea already sets in.

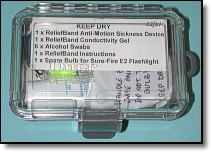

The Woodside Biomedical ReliefBand uses electronic stimulus to effect relief. The new "Adventurer" model, while not waterproof, is much more water-resistant than previous models and thus okay for use inside a closed up life raft. I'd still prefer a waterproof unit, but... This did present a few problems. It had to be kept dry during the deployment phase, be protected from crushing, and some means was required to prevent inadvertently switching on the device in storage since it has a surface mount pressure sensitive switch. There was also the issue of the instructions for use that were not waterproof and were printed in such a small font size, with lots of FDA required BS and CYA, as to make it difficult to read and understand.

The Woodside Biomedical ReliefBand uses electronic stimulus to effect relief. The new "Adventurer" model, while not waterproof, is much more water-resistant than previous models and thus okay for use inside a closed up life raft. I'd still prefer a waterproof unit, but... This did present a few problems. It had to be kept dry during the deployment phase, be protected from crushing, and some means was required to prevent inadvertently switching on the device in storage since it has a surface mount pressure sensitive switch. There was also the issue of the instructions for use that were not waterproof and were printed in such a small font size, with lots of FDA required BS and CYA, as to make it difficult to read and understand.

I selected a small Otter Products 1000 series Otter Box to keep the device dry and to prevent it from being crushed. It was necessary to file the corners of the latch so the sharp corners wouldn't present a danger to the raft. An appropriately sized and trimmed thick rubber fender washer was placed over the face of the ReliefBand, with the hole over the switch, and then taped in place. Some Tyvek on the backside protected the electrical contacts from the tape. I also added some alcohol swabs (which used to be included with the device, but which are no longer) to assist in cleaning and drying out the skin where the conductive gel is applied. Generic swabs were half as thick and two-thirds the pack size of the brand name ones, and they work just fine for this use.

Using the supplied instructions, I re-wrote them slightly to make them more succinct and understandable and took photos to clearly illustrate the critical steps for use. While effective for a large majority of users, the device must be applied correctly to work and it isn't a simple procedure to do it right the first few times, so clear directions are vital. Then the new instructions and photos were pasted up and laser copied onto two sides of a sheet of Rite In The Rain waterproof paper. Voilà! Effective and waterproof instructions for use.

Using the supplied instructions, I re-wrote them slightly to make them more succinct and understandable and took photos to clearly illustrate the critical steps for use. While effective for a large majority of users, the device must be applied correctly to work and it isn't a simple procedure to do it right the first few times, so clear directions are vital. Then the new instructions and photos were pasted up and laser copied onto two sides of a sheet of Rite In The Rain waterproof paper. Voilà! Effective and waterproof instructions for use.

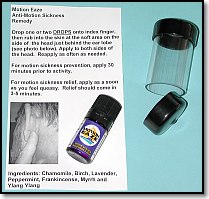

The second remedy, Alta Labs Motion Eaze, is an herbal concoction that is applied topically behind the ear. It comes in a small thick glass dropper bottle, so protection was required. Plus, it smells strongly as a result of the peppermint, lavender and other herbal extracts used, so we needed to make sure it couldn't escape. The instructions were not waterproof, nor very clear, so I rewrote them slightly and added a photo to clearly show exactly where to apply the drop or two of the remedy behind each ear. Then it was laser printed on a sheet of Rite In The Rain waterproof paper. This was folded down to size and wrapped around the bottle for cushioning, then it was all placed inside a thick crush resistant clear PVC tube, cut to length, with vinyl end caps (scrounged from a DME Corp. 747 SEP). This in turn was vacuum packed and then Winslow double vacuum packed it for a total of three layers of vacuum packaging.

The second remedy, Alta Labs Motion Eaze, is an herbal concoction that is applied topically behind the ear. It comes in a small thick glass dropper bottle, so protection was required. Plus, it smells strongly as a result of the peppermint, lavender and other herbal extracts used, so we needed to make sure it couldn't escape. The instructions were not waterproof, nor very clear, so I rewrote them slightly and added a photo to clearly show exactly where to apply the drop or two of the remedy behind each ear. Then it was laser printed on a sheet of Rite In The Rain waterproof paper. This was folded down to size and wrapped around the bottle for cushioning, then it was all placed inside a thick crush resistant clear PVC tube, cut to length, with vinyl end caps (scrounged from a DME Corp. 747 SEP). This in turn was vacuum packed and then Winslow double vacuum packed it for a total of three layers of vacuum packaging.

NOTE: I use a Tilia Foodsaver vacuum packaging machine. The price of the machine is reasonable and the performance is generally acceptable using their provided packaging materials. The biggest handicap is that you are stuck using their lightweight material that is relatively easily punctured. You can generally prevent internally caused punctures by ensuring any sharp edges or points are padded in some manner, but it's a bother and does nothing about externally originating punctures. Ideally, I'd prefer an industrial quality unit capable of using a heavier weight, tougher material. However, to date I haven't found one at an affordable price.

A spare bulb module for the flashlight Simon would have in his vest was packed in foam and placed inside the Otter box with the ReliefBand. Two spare lithium batteries for the flashlight were each individually packaged in plastic and then vacuum packed together. Twelve feet of Spectra core ultra-lightweight high test line was included since with the deletion of the rescue line there was nothing to scavenge for use in the raft to tie things in, or for improvisation or repairs.

This "Triptease LightLine" from Kelty is designed for tent guylines, but it's got some welcome attributes for our puposes. It's very light and strong for its size, only one ounce per 50 foot length of 2 mm line with a 188 pound breaking strength from that Spectra core. The exterior woven sheath resists tangling and holds knots tightly, unlike most nylon line. It also has retro-reflective 3M Scotchlite yarn woven into the sheath, which makes it easy to see at night when leaving your shelter for a nature call.

Simon would have some water in his flight suit, but I wanted to ensure he didn't suffer from dehydration. As the sole occupant, it was critical that he be able to think clearly and even minimal dehydration can have an adverse effect on judgment. The obvious solution was a Katadyn PUR Survivor 06 Manual Reverse Osmosis Desalinator (MROD), commonly referred to as a "watermaker." It turns salt water into fresh. Packed, it is about the same size as a pair of mil-spec chemical desalinator kits that turn out just barely drinkable water, and very limited quantities at that. The problem with the readily available consumer unit is that it is not easy to pump. With multiple survivors in a raft, you can at least pass it around to share the effort, but that wasn't an option for Simon.

Simon would have some water in his flight suit, but I wanted to ensure he didn't suffer from dehydration. As the sole occupant, it was critical that he be able to think clearly and even minimal dehydration can have an adverse effect on judgment. The obvious solution was a Katadyn PUR Survivor 06 Manual Reverse Osmosis Desalinator (MROD), commonly referred to as a "watermaker." It turns salt water into fresh. Packed, it is about the same size as a pair of mil-spec chemical desalinator kits that turn out just barely drinkable water, and very limited quantities at that. The problem with the readily available consumer unit is that it is not easy to pump. With multiple survivors in a raft, you can at least pass it around to share the effort, but that wasn't an option for Simon.

What we needed was the mil-spec version, the 06-LL. The military recognized the problem with the basic device and insisted on modifications to make it easier to use, especially by a lone survivor. It is virtually the same size when packed, but it includes among its modifications both handle and body extensions that make it far easier to pump and to use single-handed, albeit at a slight increase in weight and a significant increase in price. This turned out to be problematic because Katadyn had quit making this unit available to consumers. I was prepared to lend Simon my own 06-LL, but after discussing the matter with the powers that be at PUR, we arrived at a solution so that Simon received a new 06-LL for the life raft.

When it came time to pack the life raft, late word from Pains Wessex caused Winslow to be concerned about packing the EPIRB inside the raft. The company wouldn't certify that it would withstand the required compaction. While other EPIRBs, such as ACR's and Kannad's, have withstood packing just fine, without time to experiment with this new EPIRB, Winslow was leery of doing so. The solution was to pack the EPIRB in a separate pouch, tethered to inside the raft, and Velcro'd to the end of the valise. Simon would have to retrieve it from the water after deployment. Not as clean a solution as if packed inside, but workable under the circumstances. The whole thing ended up 8 x 15 x 21 inches, perfectly sized to fit its storage location.

When it came time to pack the life raft, late word from Pains Wessex caused Winslow to be concerned about packing the EPIRB inside the raft. The company wouldn't certify that it would withstand the required compaction. While other EPIRBs, such as ACR's and Kannad's, have withstood packing just fine, without time to experiment with this new EPIRB, Winslow was leery of doing so. The solution was to pack the EPIRB in a separate pouch, tethered to inside the raft, and Velcro'd to the end of the valise. Simon would have to retrieve it from the water after deployment. Not as clean a solution as if packed inside, but workable under the circumstances. The whole thing ended up 8 x 15 x 21 inches, perfectly sized to fit its storage location.

Nobody knew for sure how much the life raft would weigh in the end. We hoped to keep it to about 30 to 35 pounds, including all the survival gear. When all was done and packed, it registered only 28 pounds on the scale. Of that, the EPIRB and Survivor 06-LL weighed nearly five pounds together. I was quite pleased with the result. Simon has a very well equipped life raft that will see him through any foreseeable survival situation and at an incredibly light weight for the survival features incorporated.

I selected a Switlik Parachute Company Special Operations Vest for Simon's life vest, which we purchased from Concorde AeroSales. Switlik kindly rushed a vest through production. This is based on their Helicopter Crew Vest, but with some critical differences and additions.

I selected a Switlik Parachute Company Special Operations Vest for Simon's life vest, which we purchased from Concorde AeroSales. Switlik kindly rushed a vest through production. This is based on their Helicopter Crew Vest, but with some critical differences and additions.

The cover for the twin yellow inflation bladders (38 lbs. buoyancy total) is three-layer Nomex, which is much more comfortable to wear, especially for long periods, if not as long lasting or as tough as the conventional coated nylon material used in the standard vest. A HEED (Helicopter Emergency Egress Device, essentially a mini-SCUBA) holster is built into the vest, slightly reducing the size of one of the two equipment pockets. Adjustable leg straps are added for greater security and it has beaded looped inflation handles for better grip and easier inflation. The bladders are edged in retro-reflective material so the survivor is more easily located at night. A TSO'd locator light, USCG approved folding knife and whistle and mil-spec 2 x 3 in. glass signal mirror are also included.

We started off by making a couple changes to the vest. While these used to be available sized, they now offer only Extra Large and users are expected to just pull in the adjustment straps. On Simon that left nearly 10 inches of excess mesh material on both sides. Simon took the vest to Perez Camping & Sporting Equipment Repair and they did a very nice job of replacing the excess with a sewn-in piece of neoprene dry suit material, giving Simon a much better and more comfortable fit. Some double-sided Velcro wrapped around the adjustment straps served as keeper so they didn't just dangle and get in the way. We also ditched the attached survival gear, substituting our own.

The conventional TSO'd water activated chemical battery locator light was replaced with an Ocean Safety Limited lithium battery powered SOLAS grade Aqua-Spec locator light courtesy of the U.S. distributor, Sporting Lives. This unit weighs less, its flashing light is brighter and more visible, and it has a reliable on-off switch. Normally the switch is placed in the on position. Since Simon was flying only in the daytime and we wanted to have the light available should he end up in the water long enough for night to fall, we set the switch to off. A pull ring was added to easily remove the switch lock to allow Simon to switch the light on if required.

The conventional TSO'd water activated chemical battery locator light was replaced with an Ocean Safety Limited lithium battery powered SOLAS grade Aqua-Spec locator light courtesy of the U.S. distributor, Sporting Lives. This unit weighs less, its flashing light is brighter and more visible, and it has a reliable on-off switch. Normally the switch is placed in the on position. Since Simon was flying only in the daytime and we wanted to have the light available should he end up in the water long enough for night to fall, we set the switch to off. A pull ring was added to easily remove the switch lock to allow Simon to switch the light on if required.

A HEED III (mil-spec version of the Spare Air) by Submersible Systems was also procured from Concorde AeroSales, then inspected and filled at a local dive shop, All Wet Scuba. The vest equipment pockets were filled with signaling gear for the most part, all of it tethered to the vest through the provided sewn lanyard holes, one on each end of each pocket. Tethers were yellow braided UV resistant poly line, which won't absorb water. The attachment loops were formed using a bowline knot, then each was sealed using heat shrink tubing, ensuring it wouldn't come undone.

The left hand pocket, behind the HEED, includes a 3 x 5 inch Survival Inc. mil-spec Star Flash signal mirror, an All-Weather Whistle Company Windstorm survival whistle and a Rescue Technologies 6 in. x 40 ft. RescueStreamer. It was vacuum packed to reduce the bulk and get it small enough to fit in the pocket.

The left hand pocket, behind the HEED, includes a 3 x 5 inch Survival Inc. mil-spec Star Flash signal mirror, an All-Weather Whistle Company Windstorm survival whistle and a Rescue Technologies 6 in. x 40 ft. RescueStreamer. It was vacuum packed to reduce the bulk and get it small enough to fit in the pocket.

With space and weight at a premium, and being as it was for back-up or last-mile signaling purposes, the generally good performing, inherently buoyant Star Flash signal mirror made more sense than the superior performing, but considerably bulkier and heavier Rescue Reflectors mirror that would be even bulkier for the buoyant model. A Storm whistle would be somewhat louder than the smaller Windstorm, but was too large to fit. These are the sorts of trade-offs you make assembling a custom survival kit within tightly defined parameters.

Also in this pocket is the MicroPLB. It was attached to its tether with a quick release clip so that it could be easily transferred between the flight suit and the vest, as needed.

The right hand pocket is divided into a forward and rear compartment. The forward compartment contains the aerial flares. I settled on the Pains Wessex Miniflare 3 kit as providing the most bang for the volume and weight. I considered also Orion's Pocket Rocket and the Skyblazer XLT. The Pocket Rocket provides performance comparable with the Mini-flare, and at slightly less weight per unit, but it would have required me to fabricate some sort of container, while the Mini-flare is already nicely packed. The XLTs just didn't provide enough performance increase for the reduction in quantity that Simon would be able to carry for the same weight and bulk.

The right hand pocket is divided into a forward and rear compartment. The forward compartment contains the aerial flares. I settled on the Pains Wessex Miniflare 3 kit as providing the most bang for the volume and weight. I considered also Orion's Pocket Rocket and the Skyblazer XLT. The Pocket Rocket provides performance comparable with the Mini-flare, and at slightly less weight per unit, but it would have required me to fabricate some sort of container, while the Mini-flare is already nicely packed. The XLTs just didn't provide enough performance increase for the reduction in quantity that Simon would be able to carry for the same weight and bulk.

Two Miniflare 3 kits were included, a total of 16 flares that would be typically launched as pairs with approximately 10 seconds between launches, but only one of the relatively heavy launchers. In addition, I removed the plastic labels and carefully cut down the rubber holders to bare minimum, saving quite a bit of unnecessary weight.

Two Miniflare 3 kits were included, a total of 16 flares that would be typically launched as pairs with approximately 10 seconds between launches, but only one of the relatively heavy launchers. In addition, I removed the plastic labels and carefully cut down the rubber holders to bare minimum, saving quite a bit of unnecessary weight.

The meteor cartridges themselves were all carefully oriented with the tangs perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the case. When the launcher is held in the most natural position, the trigger stud is facing towards the operator. Holding the case in its natural position, given the orientation of the person in the water and the lanyard attaching it to the vest pocket, the case is vertical. It then all falls nicely to hand in a consistent manner each time. A quarter turn of the launcher and the cartridge is locked into place.

Also in the front compartment went a safety "zip" knife (a Hoover Industries raft knife) in a slide-in holster (fabricated by Winslow). This would allow Simon to safely cut loose used flares and such. By retaining the holster on the tether it couldn't be lost and he could easily slide the knife back in for safekeeping.

In the rear compartment are the handheld flares. I considered using the mil-spec Mk 13 Mod 0 Day/Night flare or the comparable plastic cased Pains Wessex Mk 4, but both have serious shortcomings, the most significant being they don't burn very long and the smoke is not very effective at all. Moreover, they are bulky. Most other handheld flares are far too long, except for one.

In the rear compartment are the handheld flares. I considered using the mil-spec Mk 13 Mod 0 Day/Night flare or the comparable plastic cased Pains Wessex Mk 4, but both have serious shortcomings, the most significant being they don't burn very long and the smoke is not very effective at all. Moreover, they are bulky. Most other handheld flares are far too long, except for one.

Comet makes a slim (1 in. diameter) SOLAS Red Handheld Flare available with a folding wire handle, but it is distributed primarily in Europe. While the U.S. importer, Orion, only brings in these flares with plastic handles, I had some older expired flares with the folding handles. The body of the flare is essentially the same, the extended plastic handles just screw onto the bottom. Marisafe supplied current flares, I provided the handles. Unscrew the plastic handles, slip the wire folding handles into the existing holes and we were in business. These SOLAS flares burn very brightly for a full minute; I included three of them.

However, I didn't just toss the plastic handles, I had plans for them. The flares are not light and were something of a bother to manage in the pocket. Due to their length (6.88 in.) and thus the inability to close the pocket's Velcro'd closure flap all the way, it would have been relatively east for one of the slim flares to slip out. The solution was to fabricate a holder for the flares. The cut-off tops of the plastic handles were riveted and epoxied to a piece of aluminum angle which was trimmed to fit with all the edges blended and smoothed so they wouldn't cut the fabric of the vest or poke through. Spacing just allowed for the units to rotate without interference. The threaded portion was trimmed down until it took one complete 360-degree rotation to release the flare. That was enough thread to secure the flare while still making it easy to release without having to remove the entire assembly from the pocket. Then, before permanently affixing them, the folded handles wwere aligned along the axis of the holder while tightened down and the position marked and the pieces numbered and matched to the flares before permanently affixing them. Each flare was tethered, care being taken to wind the tether in the right direction so it unwound as the flare was unscrewed from the holder.

However, I didn't just toss the plastic handles, I had plans for them. The flares are not light and were something of a bother to manage in the pocket. Due to their length (6.88 in.) and thus the inability to close the pocket's Velcro'd closure flap all the way, it would have been relatively east for one of the slim flares to slip out. The solution was to fabricate a holder for the flares. The cut-off tops of the plastic handles were riveted and epoxied to a piece of aluminum angle which was trimmed to fit with all the edges blended and smoothed so they wouldn't cut the fabric of the vest or poke through. Spacing just allowed for the units to rotate without interference. The threaded portion was trimmed down until it took one complete 360-degree rotation to release the flare. That was enough thread to secure the flare while still making it easy to release without having to remove the entire assembly from the pocket. Then, before permanently affixing them, the folded handles wwere aligned along the axis of the holder while tightened down and the position marked and the pieces numbered and matched to the flares before permanently affixing them. Each flare was tethered, care being taken to wind the tether in the right direction so it unwound as the flare was unscrewed from the holder.

Also in the rear compartment is a Laser Products Sure-Fire E2 double DL123A lithium cell flashlight. This was selected because it provided by far the brightest beam for the size and weight and a reasonable run time for signaling purposes. Plus, it could be easily switched via the rotating butt cap with one hand. There were a few problems with the standard E2, aside from the fact that it really wasn't yet in volume production.

Also in the rear compartment is a Laser Products Sure-Fire E2 double DL123A lithium cell flashlight. This was selected because it provided by far the brightest beam for the size and weight and a reasonable run time for signaling purposes. Plus, it could be easily switched via the rotating butt cap with one hand. There were a few problems with the standard E2, aside from the fact that it really wasn't yet in volume production.

The momentary switch did not have a lock-out position, as do all the tactical Sure-Fire lights, and as a result it also wasn't totally waterproof. The momentary switch also meant it could inadvertently be turned on in the pocket, not a desirable feature for such survival gear. Finally, the lanyard adapter wasn't yet available, even in prototype form. Laser Products agreed to make up an E2 for Simon with a custom solid butt cap incorporating an integral lanyard hole that neatly solved all three problems. The end result was just about perfect.

Also stored in this compartment are a one-ounce plastic bottle of SPF 45 sunscreen and a SPF 30 lip balm that is retained using a little neoprene "glove." After placing everything in the pocket, the flashlight rattled against the flare holder so I added short piece of split fuel line tubing to the edge of the holder, silencing the rattle.

Also stored in this compartment are a one-ounce plastic bottle of SPF 45 sunscreen and a SPF 30 lip balm that is retained using a little neoprene "glove." After placing everything in the pocket, the flashlight rattled against the flare holder so I added short piece of split fuel line tubing to the edge of the holder, silencing the rattle.

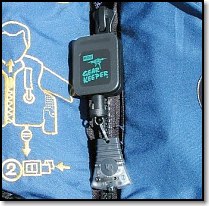

Using a Hammerhead Industries pin mount Mini Gear Keeper auto-retractable lanyard, I attached a CMG Equipment waterproof Q-4 LED Mini Task Light to the zipper truck. We used these Gear Keepers in a number of locations in N7UM for tethered security of various items.

All together, the vest and its equipment weighed just eight pounds. Despite all the gear and bulk, Simon found the Switlik vest to be very comfortable while seated in the aircraft.

Simon was flying from the left seat, somewhat unusual for helicopters, but normal for the Hughes 500. The life raft would be secured in the right seat with the belt and harness, easily accessible if needed. When Simon is not wearing the Switlik vest, it will be draped around the life raft valise and then both will be secured under the belts and harness. Both will then be available for a quick egress.

Simon was flying from the left seat, somewhat unusual for helicopters, but normal for the Hughes 500. The life raft would be secured in the right seat with the belt and harness, easily accessible if needed. When Simon is not wearing the Switlik vest, it will be draped around the life raft valise and then both will be secured under the belts and harness. Both will then be available for a quick egress.

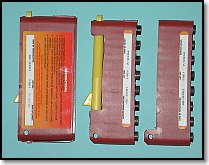

I arranged for a Schroth Safety Products Water Activated Buckle for Simon's safety harness. This unit simply replaces the existing buckle. It provides a back-up automatic release of the belts after a specified period of immersion, in this case 9.5 seconds, well after he would normally have egressed the helo in a ditching. This would be the first commercial application for this device. A second water activated buckle, designed to release all the belts, will be added to the right side for securing the life raft. Releasing all the belts means there is nothing to possibly hang up on the life raft valise when time to egress.

Moving from the overwater survival gear, we needed to assemble some basic survival and medical gear and supplies that would see Simon though any likely scenario for a limited period, unlikely to be longer than 24 hours. Simon is not a survival expert, but is smart and self sufficient with some outdoors experience, so the gear selected needed to be more than just the essentials, but not a whole lot more.

A sturdy knife being the most basic survival tool, the first question to be answered was if it was to be a folder or fixed blade. A myriad of practical and political reasons made a folder the only reasonable choice. A Chris Reeve Sebenza would fit the bill--strong, reliable and relatively lightweight with its solid titanium body and integral lock.

A sturdy knife being the most basic survival tool, the first question to be answered was if it was to be a folder or fixed blade. A myriad of practical and political reasons made a folder the only reasonable choice. A Chris Reeve Sebenza would fit the bill--strong, reliable and relatively lightweight with its solid titanium body and integral lock.

Finding a left-handed Sebenza is not always easy, so I went to the source. Even that doesn't always guarantee success. They not only didn't have one, but there were none scheduled for production anytime soon. However, after conferring with Chris and in consideration of Simon's situation, Anne advised they could do one up special within our time frame. In a few weeks Simon was the proud and very appreciative owner of a large, left-handed Sebenza.

Simon already owned a Victorinox Swiss Champ with the SOS Kit and decided he preferred his well-used decade old friend to a new multi-purpose tool. Since it was adequate for the job, there was no need to argue the issue. All I needed to do was touch up the blades. The gear in the SOS kit was of limited usefulness, and I discounted is almost entirely. As with some other gear selections, the client sometimes dictates one item over another based on their own experience, priorities or personal preferences. A Leatherman Wave, for example, would have saved 1.5 ounces, a Swiss Tool half an ounce, both offering potentially more functionality.

There was already a Leatherman Super Tool in N7UM, but it was mounted on the passenger side, out of reach of Simon, and therefore discounted as not necessarily available if needed in an emergency.

Given that portions of the terrain Simon would over-fly would be tropical in nature, a machete seemed in order. Unfortunately, the typical machete is not exactly a lightweight. The solution would be one of Ross Aki's beautiful custom made lightweight ATS-34 stainless steel Straight Back Machetes in a Kydex sheath. Unfortunately (for us, not him), Ross has a significant backlog of orders. Fortunately, he was willing to loan Simon his own personal machete for the race, until he could get around to making one for him.

Given that portions of the terrain Simon would over-fly would be tropical in nature, a machete seemed in order. Unfortunately, the typical machete is not exactly a lightweight. The solution would be one of Ross Aki's beautiful custom made lightweight ATS-34 stainless steel Straight Back Machetes in a Kydex sheath. Unfortunately (for us, not him), Ross has a significant backlog of orders. Fortunately, he was willing to loan Simon his own personal machete for the race, until he could get around to making one for him.

We placed the machete out of the way under Simon's seat with the handle just sticking out enough to grab. Secured in place with some large Velcro patches, a quick sideways yank or shove on the handle will break it loose and then Simon can just pull out the sheath and machete as a unit.

A BCB Deluxe Commando Wire Saw was included for use in more temperate areas.

Redundancy is important for fire starting. We started with an Essential Gear Windmill waterproof/windproof butane lighter as the primary ignition source. Quick and easy, the more basic flint and steel alternatives would be back-up to this. The lighter has another, less critical purpose, to seal the ends of the Spectra line when cut. Like all high-tech line, the ends fray badly when cut. For emergency use you just tie a knot in the end, but melting it is better.

Primary back-up is a Four Seasons Survival Spark-Lite kit with one-handed flint firestarter and tinder. For pocket carry I added a Done Right Manufacturing Sparky/Military Match, tossing the superfluous piece of hacksaw blade (Simon has plenty of sharp edges to use) and sealing the flint and magnesium rod inside some clear shrink tubing. One way or another, Simon would be able to warm himself at a fire or light a signal fire. This arrangement pretty much duplicates what I normally carry.

Given the expected short duration of any survival situation, the moderate temperatures and Simon's ample personal reserves, food was not an issue. Water, however, was very much a concern, particularly for the desert and overwater portions of the flight. We settled on a pair of 16-ounce plastic flasks with curved backs that would fit comfortably in the lower flight suit pockets. These were sterilized with iodophor and then filled with purified (reverse osmosis) and boiled water that was poured in while still boiling and then sealed. Since we didn't have to worry about freezing, the flasks were filled to the top, getting in every precious drop I could. As the water cooled, it created a slight vacuum, ensuring a tight seal. The metal screw-on shot glasses that came with the flasks were tossed.

Given the expected short duration of any survival situation, the moderate temperatures and Simon's ample personal reserves, food was not an issue. Water, however, was very much a concern, particularly for the desert and overwater portions of the flight. We settled on a pair of 16-ounce plastic flasks with curved backs that would fit comfortably in the lower flight suit pockets. These were sterilized with iodophor and then filled with purified (reverse osmosis) and boiled water that was poured in while still boiling and then sealed. Since we didn't have to worry about freezing, the flasks were filled to the top, getting in every precious drop I could. As the water cooled, it created a slight vacuum, ensuring a tight seal. The metal screw-on shot glasses that came with the flasks were tossed.

I repackaged 24 tablets of Potable Aqua disinfectant to treat any water from natural sources.

With bugs a potential problem over a large portion of the route, some means to deal with them is necessary. For mosquitoes and such, 100% DEET remains the gold standard, so in went a bottle of that. Before packing it, I carefully cut away the child-proof portion of the cap and then trimmed what remained, both to save weight and bulk and for easier access.

With bugs a potential problem over a large portion of the route, some means to deal with them is necessary. For mosquitoes and such, 100% DEET remains the gold standard, so in went a bottle of that. Before packing it, I carefully cut away the child-proof portion of the cap and then trimmed what remained, both to save weight and bulk and for easier access.

A head net allows you to avoid putting the DEET on your face where a slip can cause serious tears and discomfort. I selected Outdoor Research's new Spring Ring Headnet. This headnet addresses 2 problems I've had with many such devices, they tend to be difficult to see through and are annoying as they drape over your face. Plus, the mil-spec style ones with a ring to keep the net away from your face, don't pack very compactly. As the name suggests, this one has a stainless steel ring that holds the net away from the face while also minimizing the wrinkles that impair vision.

At 12 inches in diameter, it's large enough to easily wear over a cap or hat. An elastic drawcord at the bottom allows you to easily secure it around the neck. What really sells this headnet is that the flat ring collapses down to approximately four inches with a simple twist. While not quite as compact as a design with no ring, and I'd prefer if they used a round piece of wire instead of the flat band, its performance is so much better, it's worth the little extra bulk. I vacuum packed it with the insect repellent to cut down on the bulk. It was necessary to add some protection, in the form of some poly coated nylon cloth, to prevent the ring from cutting the netting or the vacuum bag once it had been sucked down.

For primary shelter, we have the life raft with its mosquito netting if necessary. Not just for tropical areas, the sandy desert is home to plenty of bugs as many Americans discovered during Desert Storm. The raft has two drawbacks. First, it isn't on Simon's person which means it might not egress the chopper with him in an emergency. Second, while the canopy is very weathertight, it isn't very opaque and will let in a lot of sun, and heat, in a desert environment.

As back-up shelter and to serve as a sun shade, I selected an updated version of the venerable and often maligned (by me and others) emergency space blanket. The Adventure Medical version, theHeatsheet Two, has a couple of minor advantages. One, at 59 x 96 inches it is a bit larger than normal. Two, it is printed over much of one side with an orange background for the text of survival instructions. This thin coating of ink seems to help quiet it down somewhat and also gives it just a wee bit more tear resistance. Or, perhaps it's just my wishful thinking. In any case, it's biggest advantage remains its light weight and compactness, nothing else so far comes close. Sometimes, as in this case, that overcomes the drawbacks. For desert use, its reflectivity is a real godsend and the primary reason I chose it.

As back-up shelter and to serve as a sun shade, I selected an updated version of the venerable and often maligned (by me and others) emergency space blanket. The Adventure Medical version, theHeatsheet Two, has a couple of minor advantages. One, at 59 x 96 inches it is a bit larger than normal. Two, it is printed over much of one side with an orange background for the text of survival instructions. This thin coating of ink seems to help quiet it down somewhat and also gives it just a wee bit more tear resistance. Or, perhaps it's just my wishful thinking. In any case, it's biggest advantage remains its light weight and compactness, nothing else so far comes close. Sometimes, as in this case, that overcomes the drawbacks. For desert use, its reflectivity is a real godsend and the primary reason I chose it.

An REI Supplex unstructured cap, including bill, with neck cape tops off the personal sun and weather protection. I added a parachute cord neck strap with cord lock, Sue (my wife) sewing it to the provided elastic loops on the cap. I then vacuum packed it for compactness. A two-ounce plastic bottle of SPF 45 sunscreen and SPF 30 lip balm round out the sun protection assets.

A bandanna is an essential multi-purpose item for desert use, as well as elsewhere. A stiff new bandanna isn't particularly comfortable or absorbent, so I reached in my chest of drawers for one of my well used, well washed, soft red bandannas to contribute to the cause.

Relying primarily upon the electronic communications gear, only rudimentary signaling equipment is carried on Simon's person for back-up and last-mile use. A 2 x 3 inch Survival Inc. mil-spec Star Flash signal mirror, a Fox 40 International Classic Fox 40 whistle and flashlights provide adequate and compact signaling resources, day and night.

Relying primarily upon the electronic communications gear, only rudimentary signaling equipment is carried on Simon's person for back-up and last-mile use. A 2 x 3 inch Survival Inc. mil-spec Star Flash signal mirror, a Fox 40 International Classic Fox 40 whistle and flashlights provide adequate and compact signaling resources, day and night.

The primary flashlight, or more correctly flashlights since Simon has five of these spread amongst his gear (including the one on his Switlik vest, noted above), is CMG Equipment's Q-4 single white LED Mini Task Light. This light incorporated two critical attributes besides its small size, light weight, long battery life and relative brightness. One, it has a permanent on feature. Not a very sophisticated one, but it works. In addition, it is waterproof; ostensibly to only 10 feet, but I tested it to 12 with no problems and it probably does even better. Enough to likely keep the salt water out of it should Simon take a dunk. Other such lights, like my previously top rated and smaller Photon II, work after immersion in fresh water and are okay if you dry them out, but salt water is a bigger problem for them. We needed truly waterproof and the Q-4 was the only one that fit the bill at this time and that was in production, and that just barely. We received ours from the first production run only a day before Simon's departure.

For brighter point illumination there's a Pelican Products single AAA-cell Mini Mity-Lite. For brighter illumination and signaling Simon selected a Laser Products Sure-Fire E1, single DL123A lithium cell flashlight.

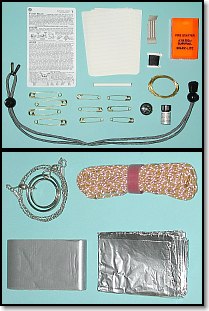

What remains is a quantity of generally useful and versatile gear and supplies. A small flat roll of duct tape allows almost anything to be fixed, or so it seems at times. Heavy-duty aluminum foil has a multitude of uses. Four large and six medium sized solid brass safety pins allow quick repairs and won't rust. There are three needles in assorted sizes plus some heavy-duty poly thread for clothing repairs.

What remains is a quantity of generally useful and versatile gear and supplies. A small flat roll of duct tape allows almost anything to be fixed, or so it seems at times. Heavy-duty aluminum foil has a multitude of uses. Four large and six medium sized solid brass safety pins allow quick repairs and won't rust. There are three needles in assorted sizes plus some heavy-duty poly thread for clothing repairs.

The remaining 32 ft. of that Spectra line we included in the raft SEP is found here. Ten feet of brass snare wire is more useful for improvisation and repairs than for snares. A BCB button compass is included, just because. Also included is a Sterling Systems Superior pocket carbide knife sharpener with the optional diamond dust pad (yes, they still make it with the pad), just in case. Knives and machetes sometimes get abused in a survival situation and it's nice to be able to touch up the blade if needed and at only a few tenths of an ounce, there's no good reason not to have it along.

Four sheets of Rite In The Rain waterproof note paper and a short stub of thin pencil were included for making notes or keeping a log. A set of Lee Nading's "Survival Cards," waterproof plastic survival instruction cards, was added to assist Simon, though I did put a line through a number of items not so well advised, such as the old cut and suck remedy for snake bites.

Some toilet paper was vacuum packed for, well, ummm, the usual uses.

Finally, I added the parachute cord lanyard from off the Sure-Fire E2 (as opposed to making one myself since we already had it). This well made lanyard has double cord locks and I added a second clip so it would be easy to hang a bunch of gear from it, such as the signal mirror, whistle and lights. They'll be safe and secure and readily accessible around Simon's neck.

Finally, I added the parachute cord lanyard from off the Sure-Fire E2 (as opposed to making one myself since we already had it). This well made lanyard has double cord locks and I added a second clip so it would be easy to hang a bunch of gear from it, such as the signal mirror, whistle and lights. They'll be safe and secure and readily accessible around Simon's neck.

Much of this smaller stuff (see photo above right) was packed in a pair of yellow plastic Trail Boxes (from Campmor - closed size 3.5 x 4.5 x 1.125 inches). These telescope to accommodate large items or more stuff. The back is curved to fit more comfortably against your body, be it leg or back pocket. However, the sharp edges aren't comfortable at all, so I carefully eased these edges with a razor knife, making them a lot more comfortable in the pocket of the flight suit and also likely less wearing on the fabric. I might have trimmed the length of the outer half of each box to save a few tenths of an ounce, but with the full length they were secure and didn't need any other security arrangements to ensure they didn't come apart, plus they could also accommodate more gear, if needed in the field or at a later date. Contents labels of waterproof paper, including the date packed, were affixed to each with rubber cement (label corners were cut to lessen chances they would come off). Filled with the gear, one weighs 6.6 ounces, the other 5.1 ounces.

Space for medical gear was limited, there are only so many pockets, so priority went to basic wound treatment and means to stop blood loss and secure an injured limb.

Space for medical gear was limited, there are only so many pockets, so priority went to basic wound treatment and means to stop blood loss and secure an injured limb.

A pair of mil-spec TrauMedic multi-purpose bandages (from Brigade Quartermasters) will take care of the big things, seven two-inch compresses serve for smaller injuries. These bandages all are designed to tie on, an advantage in a wet environment where adhesives are notoriously unreliable. Two crushable swabs of Mastisol adhesive will help bandages stick even in the wet. Five compressed super absorbent tampons provide for a lot of blood absorption and wound packing in a very compact sterile package. Seven Coverlet elastic adhesive bandages will dress smaller cuts and scrapes.

Anti-infectives include six povidone iodine swabs for disinfecting and cleaning a wound, a pair of Vionex anti-microbial wipes for clean up and area disinfectant and six packets of triple antibiotic ointment.

Some analgesics are included for any aches and pains. Vials for prescription analgesics were provided, but Simon never had time to get the prescription filled.

Some analgesics are included for any aches and pains. Vials for prescription analgesics were provided, but Simon never had time to get the prescription filled.

The two large bandages and four compresses were vacuum packed together. The remainder was put into another Trail Box and that box was vacuum packed. Unlike most of the survival gear, some of these medical supplies wouldn't do so well if they got wet.

In addition, I packed a small waterproof zipper lock vinyl Atwater Carey "Pocket Doc" first aid kit pouch with a more complete assortment of first aid supplies. Included were a variety of regular and specialty adhesive bandages, anti-infectives, analgesics and odds and ends such as safety pins for everyday first aid use and repairs. Thus Simon wouldn't be tempted to break into the survival medical gear to bandage a cut finger or scraped knuckle or to treat a similar minor injury or aches and pains. This pocket first aid kit weighs 1.9 ounces.

The total weight for all the survival gear Simon would be carrying in his flight suit is 5.1 pounds. Of that total, 2.2 lbs., or nearly half, is comprised of the two flasks of water. The MicroPLB adds nearly a half pound. The Medical supplies totaled 9.1 ounces. The Swiss Champ weighs 10.1 oz. and the Sebenza 4.9 ounces.

The total weight for all the survival gear Simon would be carrying in his flight suit is 5.1 pounds. Of that total, 2.2 lbs., or nearly half, is comprised of the two flasks of water. The MicroPLB adds nearly a half pound. The Medical supplies totaled 9.1 ounces. The Swiss Champ weighs 10.1 oz. and the Sebenza 4.9 ounces.

It's easy to assemble survival gear if weight or bulk isn't critical and you aren't all that picky about what particular gear is included. When you start getting picky, you quickly discover that nobody carries all the items you want. In fact, you often have to procure stuff from dozens of vendors, as was the case here. Sometimes the normal source didn't have stock and on such short notice couldn't provide something, so an alternative source had to be found or special arrangements made to produce it in time. Sometimes what was desired wasn't available as a production item, either at all, or just not quite yet. Special kudos to the suppliers who went above and beyond to supply us exactly the gear we needed so we didn't have to settle for lesser capabilities or more weight.

Cutting weight starts with selecting the right lightweight gear. However, that's only the the beginning. Reducing weight to minimums is often an exercise in minutia. Being a bit anal compulsive helps. Often it means hours dedicated to shaving ounces, sometimes literally, from gear. Tenths of ounces add up to full ounces and ounces add up to pounds. A fraction of an ounce here, another fraction of an ounce there and pretty soon you're talking about pounds--noticeable weight savings. When weight is critical, it's the only way to get the pounds out.

Cutting weight starts with selecting the right lightweight gear. However, that's only the the beginning. Reducing weight to minimums is often an exercise in minutia. Being a bit anal compulsive helps. Often it means hours dedicated to shaving ounces, sometimes literally, from gear. Tenths of ounces add up to full ounces and ounces add up to pounds. A fraction of an ounce here, another fraction of an ounce there and pretty soon you're talking about pounds--noticeable weight savings. When weight is critical, it's the only way to get the pounds out.

Those who have never attempted something like this might be surprised that I spent a bit over 90 hours on this project from start to finish (including some odds and ends not covered in this article). Anyone who has tried assembling something like this themselves won't be at all surprised. It doesn't assemble itself and even the simple things like packing items in a Trail Box or tieing tethers ends up taking hours to get right, often requiring mocking it up first before the final assembly or redoing it a number of times until it's just right. The devil is in the details and details take time.

Sourcing items required more time than you might expect as well, including following up on items not received when expected for myriad reasons. There were well over a 175 emails and hours of phone calls involved and they add up. If more time had been available, it would have cut down on those type situations significantly. Because of the tight time line, shipping often cost more than the items being shipped. There's a lesson for anyone attempting such a project--start early if you can.

These sorts of projects can either be a blast or a bear. It helps when you've got a good client and working with Simon was fun. He's now Equipped To Survive.

These sorts of projects can either be a blast or a bear. It helps when you've got a good client and working with Simon was fun. He's now Equipped To Survive.

You can follow Simon's adventures at www.N7UM.com. (No longer an active site.))